Bizfi Alum Jared Weitz Reflects on Demise of Former Employer and Rise of UCS

October 9, 2017 Jared Weitz has come a long way since his earlier days as one of the original Bizfi employees. Today he’s at the helm of online funding marketplace United Capital Source (UCS), which has been on a tear since AltFinanceDaily last spoke with Weitz a couple of years ago. The UCS founder and chief executive took some time to revisit with us about having to painfully watch the demise of his former employer, which is where he cut his teeth in this business, and the rise of his own company UCS as a funding marketplace.

Jared Weitz has come a long way since his earlier days as one of the original Bizfi employees. Today he’s at the helm of online funding marketplace United Capital Source (UCS), which has been on a tear since AltFinanceDaily last spoke with Weitz a couple of years ago. The UCS founder and chief executive took some time to revisit with us about having to painfully watch the demise of his former employer, which is where he cut his teeth in this business, and the rise of his own company UCS as a funding marketplace.

In some ways, the more things change the more they stay the same. Since the last time Weitz spoke with us, the company’s location remains in the heart of Times Square in New York, and UCS has grown its staff by only four people including two sales reps. What has changed, however, is the amount of funding that the company has done and the size of the average transaction, all of which have blossomed.

“When we first spoke a few years ago we were doing $8 million to $10 million a month in funding volume. Now we are doing between $14 million and $16 million per month,” said Weitz.

He added that where the company differentiates itself is that while a few years ago the products they were selling were predominately in the sub-prime space now they sell other products, which allows merchants to “swim upstream” when they qualify for that.

The result has been bolstered partnerships and product offerings and an average loan size that has jumped from $30,000 to $40,000 per deal to a range of $500,000 to $2 million.

“We opened up the funnel to the kind of relationships we’re able to broker and the kinds of financings we’re able to offer. We’re playing in the field of SBAs, account receivables financing, lines of credit and asset backed loans. By offering these products our volume has jumped significantly and allowed us to talk to different referral partners.”

UCS does all of its own marketing and generates leads for their in-house sales reps. Those sales reps take a file from open to close and they analyze the small business owner’s needs on a consultative call.

“We understand their business and their pain points. The first question we ask isn’t how much do you need but what’s paining you in your business today that we can help you with?”

One such business owner recounted his experience with UCS to AltFinanceDaily, saying that traditional banks were “an absolute pain” to secure funding. He spoke of the “very stressful” and time-consuming process of applying for a loan, saying he doesn’t have time to “jump through a million hoops to get a loan.”

“When I was initially looking to curb my temporary cash flow problem, I searched online for the best alternatives to traditional bank loans. I read all the reviews on companies and decided to call UCS,” the business owner told AltFinanceDaily, adding that he’s been a UCS repeat customer for a number of years and is especially fond of the ease at which the process is completed.

“I could literally call Jared today and have six figures in my account tomorrow. The best part is the pay back process. They only take funds when I run credit card transactions. So, in my slow months, I don’t have to stress and worry about repaying the loan. UCS is a perfect fit for me,” the business owner said.

Eye Opener

As the seventh or eighth employee of Bizfi, Weitz really has been part of the evolution of online funding. He says the rise and fall of Bizfi has been an “eye opener” for him.

“It caused a bunch of funding companies to be a little gun shy when it comes to funding. I told my guys this too shall pass. People are shaken and wondering if it’s a larger global issue. Thankfully it’s not a global issue. There are plenty of funding companies that are well backed that are still funding. My group is well able to pick it back up. We have signed up with more funding companies to increase our offerings and make sure we have no concentration issues,” said Weitz.

And although he left the company to eventually launch UCS, which has proven to be a prudent move, he has nothing but respect for his former employer.

“My history there is very deep and I’ve got a genuine love for the founders of the company. It’s where I cut my teeth. I was really sad the day I heard they’re not funding anymore.”

In fact, Bizfi was one of the funders that UCS counted among its partners.

“We had a good book there. We started to see problems and began to shift where our new business was going. Thankfully it didn’t affect me. But it showed me that you should sign up with more funding companies. If you think the mix should be X go 50% more and be super cautious. This approach has worked out for us,” he said.

Weitz has advice for other funders that might be looking to grow at lightning speed.

“Someone that’s growing so fast while they’re also innovating and looking to close larger transactions that bring them to a bigger place – that’s hard to do all at once. Driving at 200 MPH either works out well and takes you to the finish line or it doesn’t work out really well. It’s really unfortunate that it didn’t work out for them.”

Deal Competition

Deal Competition

For its part, UCS competes with the likes of LendingTree and other online marketplaces, but that seems only to add an ounce of perspective to Weitz and the UCS team, driving them to adjust and remain nimble so that they can get the next deal.

“Healthy competition is good for us. We welcome anything like that. Some of my best learning experiences have been when we were beat out on a deal. I call the merchant personally and say hey, who gave you the deal? Honestly, I want to sign up with them and offer those rates to my clients. We form a friendship with both the funder and the small businesses,” he said.

UCS also counts some high-profile funders among its partners.

“We’ve worked with some funders forever and it’s been great. But we really had to also find folks that offer certain products but at a cheaper rate,” said Weitz, pointing to the scenario of a merchant having a few of those loans under their belt and improved credit as a result. “They are being solicited by depository banks and can qualify for that rate. We don’t want to lose the relationship. My thought process is sign up with similar folks with that product and when the time comes we can swim the merchant upstream.”

For instance, not all funders offer SBA loans but UCS has been doing so for the past two years. “It’s really kind of taken off for us over the last year. The same thing with accounts receivable and future order financing.”

UCS acts as both a broker and investor in their own deals, so they have a vested interest in the underwriting standards. “Investing with some of our funding partners on the syndication side allows us to have buying power and to take an actual interest in the merchant we’re dealing with,” said Weitz, adding that UCS takes a hybrid approach offering both a fully automated underwriting process for those merchants who want it but also having the capability to talk to the business owners, which is what the large majority of business owners prefer.

The Top Small Business Funders By Revenue

September 14, 2017Thanks to the Inc 5000 list on private companies and earnings statements from public companies, we’ve been able to compile rankings of alternative small business financing companies by revenue. Companies that haven’t published their figures are not ranked.

| SMB Funding Company | 2016 Revenue | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| Square | $1,700,000,000 | $1,267,000,000 | Went public November 2015 |

| OnDeck | $291,300,000 | $254,700,000 | Went public December 2014 |

| Kabbage | $171,800,000 | $97,500,000 | Received $1.25B+ valuation in Aug 2017 |

| Swift Capital | $88,600,000 | $51,400,000 | Acquired by PayPal in Aug 2017 |

| National Funding | $75,700,000 | $59,100,000 | |

| Reliant Funding | $51,900,000 | $11,300,000 | Acquired by PE firm in 2014 |

| Fora Financial | $41,600,000 | $34,000,000 | Acquired by PE firm in October 2015 |

| Forward Financing | $28,300,000 | ||

| IOU Financial | $17,400,000 | $12,000,000 | Went public through reverse merger in 2011 |

| Gibraltar Business Capital | $16,000,000 | ||

| United Capital Source | $8,500,000 | ||

| SnapCap | $7,700,000 | ||

| Lighter Capital | $6,400,000 | $4,400,000 | |

| Fast Capital 360 | $6,300,000 | ||

| US Business Funding | $5,800,000 | ||

| Cashbloom | $5,400,000 | $4,800,000 | |

| Fund&Grow | $4,100,000 | ||

| Priority Funding Solutions | $2,600,000 | ||

| StreetShares | $647,119 | $239,593 |

Companies who were published in the 2016 Inc 5000 list but not the 2017 list:

| Company | 2015 Revenue | Notes |

| CAN Capital | $213,400,000 | Ceased funding operations in December 2016, resumed July 2017 |

| Bizfi | $79,000,000 | Wound down |

| Quick Bridge Funding | $48,900,000 | |

| Capify | $37,900,000 | Wound down |

Where Alternative Finance Ranks on the Inc 5000 List

September 14, 2017Here’s where your peers rank on the Inc 5000 list for 2017:

| Ranking | Company Name | Growth | Revenue | Type |

| 15 | Forward Financing | 12,893.16% | $28.3M | MCA |

| 47 | Avant | 6,332.56% | $437.9M | Online Consumer Lender |

| 219 | OppLoans | 1,970.22% | $27.9M | Online Consumer Lender |

| 260 | US Business Funding | 1,657.42% | $5.8M | Business Lender |

| 361 | nCino | 1,217.53% | $2.4M | Software |

| 449 | Kabbage | 979.31% | $171.8M | Online Consumer Lender |

| 634 | Lighter Capital | 712.03% | $6.4M | Online Business Lender |

| 694 | Swift Capital | 652.08% | $88.6M | Business Lender |

| 789 | CloudMyBiz | 575.46% | $2.1M | IT Services |

| 1418 | loanDepot | 286.11% | $1.3B | Online Consumer Lender |

| 1439 | Nav | 281.98% | $2.7M | Online Lending Services |

| 1731 | United Capital Source | 224.85% | $8.5M | MCA |

| 1101 | ZestFinance | 165.99% | $77.4M | Online Lending Services |

| 2050 | National Funding | 184.74% | $75.7M | Online Business Lender |

| 2572 | Blue Bridge Financial | 136.73% | $6.6M | Online Business Lender |

| 2708 | Bankers Healthcare Group | 127.51% | $149.3M | Financial Services |

| 2714 | Tax Guard | 127.02% | $9.9M | Financial Services |

| 2728 | Fora Financial | 125.81% | $41.6M | Online Business Lender |

| 2890 | Reliant Funding | 121.61% | $51.9M | Online Business Lender |

| 4005 | Cashbloom | 70.47% | $5.4M | MCA |

| 4945 | Gibraltar Business Capital | 42.08% | $16M | MCA |

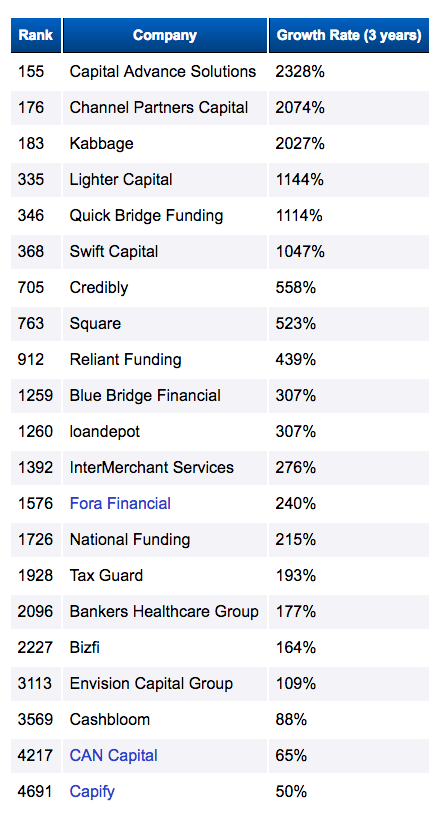

Compare that to last year’s list below:

Of the companies on the 2016 list, Capify and Bizfi were wound down while CAN Capital ceased operations but then later resumed them more than half a year later.

Sunshine and Deal Flow: Who’s Funding in Puerto Rico?

September 1, 2016

Lots of small businesses need capital in Puerto Rico and not many companies are trying to provide it. Combine that with the island’s tax incentives, tourist attractions and gaggle of ambitious entrepreneurs, and America’s largest unincorporated territory can seem like an archipelago of opportunity for the alternative small-business finance community – a virtual paradise.

But for alt funders, the sunshine, sandy beaches, swaying palms, picturesque rocky outcroppings, rich history and renowned cuisine can’t change two nagging facts about this tropical commonwealth that 3.4 million people call home. Alternative finance remains largely unknown on the island, and it’s difficult if not impossible to split credit card receipts there.

Let’s start with the good part. “If you call a restaurant in Los Angeles at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, you’re the 15th person to call them that day, but if you’re calling a business in Puerto Rico, you might be the only one,” says Andrew Roberts, director of partnership development for Merchant Cash Group, which funds some deals on the island. “So it’s not the same cutthroat competitiveness that we have here.”

But consumers in Puerto Rico’s tourist areas rely on PIN debit cards, which don’t qualify for split funding between merchants and finance providers because the cards don’t have Visa or MasterCard logos and thus merchants can’t run them as credit transactions, Roberts says. Besides, processors on the island don’t want to split the revenue from credit card transactions between funders and merchants, either, Roberts notes. “If there’s a processor in Puerto Rico that will split fund, I haven’t been unable to find them,” he says. “Believe me, I have looked.”

The two main processing platforms on the island, Global and First Data, require ISOs to carry 100 percent of the risk on a split, according to Elevate Funding CEO Heather Francis, who was involved in the island market at another company before taking her current job. That’s why split remittance “remains almost nil” in Puerto Rico, she says.

Splitting funds by using a “lockbox” – which works like an escrow account and distributes a certain percentage of receipts to the merchant and the rest to the funder – doesn’t provide a solution because banks in Puerto Rico decline to use the option, Roberts maintains. That’s why he advises that it’s easier to offer ACH-based products on the island.

Merchants on the island have to meet the same requirements for ACH that apply on the mainland, Roberts notes. That includes a reasonable number of checks returned for non-sufficient funds and a reasonable number of negative days. “The underwriting procedure on the island is pretty much the same as it is here,” he says.

Perhaps the difficulties of setting up the split in Puerto Rico shouldn’t cause any uneasiness about entering the market because the bulk of alternative funding on the island relies on daily debits—just as it does on the mainland, Roberts says. Still, he notes that some merchants in both places may qualify for split funding but fail to measure up for daily debit.

Though merchants and funders have those commonalities, the banking systems differ on the mainland and on the island. Banco Popular, which has held sway in Puerto Rico for nearly 120 years, controls much of the island’s banking and inhibits the growth of alternative funding for small businesses there, Francis says. Still, Puerto Rican merchants should have some familiarity with alternative finance or high-fee products because of the island’s high concentration of title loan companies, she notes.

Though merchants and funders have those commonalities, the banking systems differ on the mainland and on the island. Banco Popular, which has held sway in Puerto Rico for nearly 120 years, controls much of the island’s banking and inhibits the growth of alternative funding for small businesses there, Francis says. Still, Puerto Rican merchants should have some familiarity with alternative finance or high-fee products because of the island’s high concentration of title loan companies, she notes.

Similarities and and differences aside, the Puerto Rican market provides a little business to some mainland alternative finance companies. United Capital Source LLC, for example, has completed five deals for small businesses on the island, says CEO Jared Weitz. Companies can provide accounts receivable factoring there, he says.

Alternative funding has yet to post runaway growth in Puerto Rico, Weitz says, because it’s not marketed strongly there, only a few mainland funders are willing to do business in Puerto Rico, the range of products offered there is limited, and small business remains less prevalent there than on the mainland.

But a handful of mainland-based companies have been willing to take on the uncertainties of the Puerto Rican market, and Connecticut-based Latin Financial LLC serves as an example of an ISO that has enthusiastically embraced the challenge. The company got its start in 2013 by offering funding to Hispanic business people on the mainland and began concentrating on Puerto Rico early in 2015, says Sonia Alvelo, company president.

But a handful of mainland-based companies have been willing to take on the uncertainties of the Puerto Rican market, and Connecticut-based Latin Financial LLC serves as an example of an ISO that has enthusiastically embraced the challenge. The company got its start in 2013 by offering funding to Hispanic business people on the mainland and began concentrating on Puerto Rico early in 2015, says Sonia Alvelo, company president.

Alvelo built a strong enough portfolio of business on the mainland that funders were willing to take a chance on her and her customers in Puerto Rico. Latin Financial now maintains a satellite office on the island, and the company generates 90 percent of its business there and 10 percent on the mainland.

Latin Financial has a sister company called Sharpe Capital LLC that operates on the mainland, says Brendan P. Lynch, Sharpe’s president. Alvelo describes Lynch as her business partner, and he says he’s started several successful ISOs. He credits her with helping Puerto Rican customers learn to qualify for credit by keeping daily balances high and avoiding negative days.

“It’s a small company with a big heart,” Alvelo says of Latin Financial. She was born in Puerto Rico and came to Connecticut at the age of 17. “For me it’s home,” she says of the island. She’s realizing a dream of bringing financial opportunity to business owners there.

To accomplish that goal, Alvelo spends much of her time teaching the details of alternative finance to Puerto Rico’s small-business owners, their families, their accountants and their attorneys. “You want to make sure they understand,” she says, adding that the hard work pays off. “My clientele is fantastic,” she says. “I get a lot of referrals.”

Latin Financial started small in Puerto Rico when a pharmacy there contacted them to seek financing, Alvelo says. It wasn’t easy to get underway, she recalls, noting that it required a lot of phone calls to find funding. Soon, however, one pharmacy became three pharmacies and the business kept growing, branching out to restaurants and gas stations. Already, some merchants there are renewing their deals.

Growth is occurring because of the need for funding there. Puerto Rican merchants have had the same difficulties obtaining credit from banks as their peers on the mainland since the beginning of the Great Recession, Alvelo says. “It’s the same story in a different language,” she notes.

Growth is occurring because of the need for funding there. Puerto Rican merchants have had the same difficulties obtaining credit from banks as their peers on the mainland since the beginning of the Great Recession, Alvelo says. “It’s the same story in a different language,” she notes.

Speaking of language, Alvelo considers her fluency in Spanish essential to her company’s success in Puerto Rico. “You have to speak the language,” she insists. “They have to feel secure and know that you will be there for them,” she says of her clients. Roberts agrees that it’s sound business practice to conduct discussions in the language the customer prefers, and his company uses applications and contracts printed in Spanish. At the same time, he maintains that it’s perfectly acceptable to conduct business in English on the island because both languages are officially recognized.

People in Puerto Rico have been speaking Spanish since colonists arrived in the 15th Century, and English has had a place there since the American occupation that resulted from the Spanish-American War in 1898. Still, more than 70 percent of the residents of Puerto Rico speak English “less than well,” according to the 2000 Census, but that’s changing, Alvelo says.

Whatever the linguistic restraints, the products Latin Financial offers in Puerto Rico have been short-term, most with a minimum of six-month payback and a maximum of 12 months, but Alvelo hopes to begin offering longer duration funding. She also believes that split funding will come to Puerto Rico. “It’s in the works,” she asserts, noting that she is campaigning for it with the banks and processors.

At the same time, mainland alternative finance companies are learning that the threat of Puerto Rican government default does not mean merchants there don’t deserve credit, notes Lynch. “Just because the government is having trouble paying its bills,” he says, “doesn’t mean these merchants aren’t successful. The island is full of entrepreneurs.” In fact, many of Puerto Rico’s merchants use accountants and keep their business affairs in better order than their mainland counterparts do with their homemade bookkeeping.

Alvelo also knows many merchants there are worthy of time and investment. She strives to listen to her customers when they express their needs and then help them fill those needs. “I’m very, very proud to be doing this in Puerto Rico now,” she says.

Motivating Your Sales Force – Tips From the Floor

August 30, 2016

Fancy steak dinners, electronic devices and cold hard cash are just some of the ways ISOs and funders these days are motivating sales reps to bring in business.

Although it’s largely a field for self-starters, many companies find that even small tokens of appreciation do wonders to increase rep productivity. “Waving a carrot in front of your reps can make a massive difference,” says Zachary Ramirez, branch manager of the Costa Mesa, California branch of World Business Lenders, an ISO and a lender.

When it comes to motivating sales reps, every company does things slightly differently. Some have more established incentive programs, while others are more ad hoc, depending on how the day, week or month is shaping up. The common goal of all the programs, however, is to give a little something to get something greater in return.

Ramirez remembers one sales rep who won a trip to Las Vegas and then continued to be the top rep for three months running. “Those types of rewards can keep a sales team motivated, hungry and excited,” he says.

From time to time, Ramirez offers rewards such as a small cash bonus if a rep meets certain metrics like getting three submissions in a day or multiple fundings in a week. In addition, whenever his reps, who are all hourly employees, hit key performance indicators, Ramirez rewards them with a poker chip. After they accumulate enough, they can trade in their chips for various prizes. Twenty-five poker chips might be worth a flat-screen TV and 50 chips could be an expense-paid trip to Las Vegas, for example.

When it comes to motivation, it’s important to incentivize the correct behavior, Ramirez says, noting that in his earlier years running an ISO, he used to reward reps based on the number of calls they made in a day rather than applications, approvals or fundings.

The latter represent a much more serious commitment and are worth motivating for as opposed to simply making a phone call, where the outcome is uncertain. “Even if they make as many as 500 phone calls in a day, it’s irrelevant if they are not moving the transactions forward by getting applications and bank statements,” he says.

It’s also very important to have clear-cut expectations; reps need to know the consequences of not performing, Ramirez says. Most top salespeople won’t need the stick. But it’s still necessary for them to know the policies, he says.

THE POWER OF SELF-ORIGINATION

One major way United Capital Source incentivizes its 15-person sales force is by self-originating leads. It provides its reps—who are all W2 employees—with merchants that are actively expecting phone calls as opposed to handing them a laundry list of names to pitch which may or may not pan out. It costs more for United Capital to do this, but it works well for the company and for its sales force, says Jared Weitz, chief executive of the New York-based alternative-finance brokerage.

“It enables us to put our guys in a position where they are growing with the company and the company is growing as well,” he says.

In addition, United Capital has an aggressive pay structure that allows salespeople to grow with the company. For instance, the pay plans are all based on how the company is doing overall, as opposed to an individual salesperson’s performance. In this way, it encourages the sales force to work together, as opposed to each person being out for himself. Weitz says its sales team understands that if the company hits x, the sales team gets y. United Capital also offers competitive healthcare and 401(k) plans and there’s no vesting period for employees to receive their 401(k) employer match. Additionally, the company does small things like Friday lunches on the company’s dime as a thank you for time spent. It’s another way to keep the sales team happy, Weitz says.

Fundzio, an alternative funder in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, also works very hard to make sure it keeps up its pipeline of fresh leads so that reps don’t have to do that on their own. Indeed, Fundzio provides them with between seven and ten fresh and promising revenue-earning opportunities each day. This helps tie the reps to Fundzio because they have a continuous stream of business and don’t have to find it on their own.

“It guarantees them at bats every day,” says Edward Siegel, founder and chief executive of Fundzio. It also helps tie the reps to Fundzio because they have constant business. “The key thing is having new leads,” he says.

Additionally, anyone who funds a deal gets to spin a wheel in the office at the end of the business day and earn cash or special prizes like concert tickets or a fancy dinner or a $200 gift certificate. Reps really appreciate getting those prizes, which is evident when they come back to work after enjoying their steak dinner at a Fort Lauderdale waterfront restaurant. “I think it creates a fun and relaxed atmosphere feeling. A little bit goes a long way,” Siegel says.

Additionally, anyone who funds a deal gets to spin a wheel in the office at the end of the business day and earn cash or special prizes like concert tickets or a fancy dinner or a $200 gift certificate. Reps really appreciate getting those prizes, which is evident when they come back to work after enjoying their steak dinner at a Fort Lauderdale waterfront restaurant. “I think it creates a fun and relaxed atmosphere feeling. A little bit goes a long way,” Siegel says.

One way Fundzio motivates reps from the get-go is to bring them on initially as independent contractors. If they prove themselves over a 90-day period, they have the opportunity to become an employee. At any given time, the company has about 20 to 25 sales reps, representing a combination of contractors and W2 employees.

Another way Fundzio helps motivate reps is by allowing them to earn residuals from repeat business for the life of the account as long as they are still employed by the funder. Many funders have renewal departments and reps don’t directly benefit when a customer does repeat business, but that’s not the case at Fundzio, Siegel says.

REVVING UP SALES WITH CONTESTS

Certainly, to succeed in the alternative finance industry, sales reps have to be self-starters. It’s a key requirement to do the job well, in part because so many shops are purely commission-based. Nonetheless, many companies find it helps to grease the wheel a bit—regardless of whether reps are independent or W2 employees.

Fast and Easy Funds, for instance, holds weekly contests to encourage its internal sales force of 15 independent contractors. One week the contest may be for the rep with the most dials, another week it’s for the most submissions and another week for the highest number of deals funded. Each contest pays in the vicinity of $150 to $250 cash. “Every week I change it up. They don’t know what the contest is going to be until the last day of the week,” says David Avidon, president of Fast and Easy Funds, a broker and alternative funder in Boca Raton, Florida.

iAdvanceNow, a brokerage firm in Uniondale, New York, runs daily, weekly and monthly bonuses for its 38-person sales force. For instance, if a rep submits two completed deals for approval in a day he or she might get $100 cash; for three completed deals, the cash bonus might be $250, says Eddie Hamid, president of iAdvanceNow.

On a weekly basis, for submitting six complete files, reps get one spin on a big Wheel of Fortune-like apparatus in the office. Everybody is a winner; the prize depends on where the arrow lands. It may be a cash prize of $20, $50, $100 or a physical prize like a 40 inch-Samsung TV, an Apple Watch or iPad, Hamid explains.

On a monthly basis, meanwhile, each team of five to seven sales reps has a goal. If as a team they reach their goal, they get $1,500. Additionally, the top producer of the month—provided he or she has achieved a minimum of three merchants being funded—receives the top producer bonus of $1,500. The runner-up receives a $1,000 bonus and the third place sales rep receives $500. The top team in the office also gets a steak dinner at a local establishment, Hamid says.

The system works because it gives them a drive to obtain a goal while also encouraging friendly competition, says Hamid, noting that he once overheard reps talking about how much they value being named the top producer. “With sales people, they are more concerned with the recognition than the prize or the money they are receiving,” he says.

iAdvance has been in business for about two years. The current motivational system has been in place for about a year-and-a-half and it seems to work very well to motivate the sales force, Hamid says. In addition, if they are having a down sales month, Hamid ups the ante for the daily goals, adding not only cash, but also prizes.

These techniques all help to light a fire under the sales force, he says.

STRATEGIES FOR SLOW DAYS

STRATEGIES FOR SLOW DAYS

Sometimes around 3 p.m., if he feels like the room is starting to quiet, Jordan Lindenbaum, director of sales at Excel Capital Management in New York, a business financing ISO, might offer $20 or $30 cash for the next submission. Or he might offer $40 to $50 for two or three submissions by the end

of the day.

“All it takes is one slow day to kill the energy of a sales rep,” he says.

Lindenbaum finds that motivation checkpoints seem to work well. For instance, at the end of the month, the firm commonly gives a $200 bonus to the sales rep with the most submissions. For actual deals funded, Excel Capital is also working to implement a more concrete revenue-based bonus system as well, Lindenbaum says.

Excel Capital works with independent ISOs in addition to its in-house staff to bring in business. To encourage independent ISOs to refer business, the funding company offers higher payouts to those who consistently bring in high quality deals than to ISOs who bring in deals sporadically.

Chad Otar, co-founder and managing partner at Excel Capital, says a key piece of motivating sales reps is to make sure the sales manager feels motivated as well. Accordingly, the firm also makes sure to motivate Lindenbaum with larger payments for doing an outstanding job of motivating the sales force to bring in deals. “We need to motivate the sales manager so the sales manager motivates the people on the phone. It’s a chain effect. You motivate one and it motivates the others,” he says.

Excel Capital also believes in the power of team rewards. Recently, for instance, company executives treated all staffers to a steak dinner at Delmonico’s in New York City. “We’ve done it many times so our team knows they are appreciated and that our goals were met because everyone worked together,” Otar says.

THE SALARY VS COMMISSION CONUNDRUM

Paying reps a base salary in addition to commissions is another strategy some ISOs use to motivate sales reps. A salary is especially meaningful to reps just starting out, notes Ramirez of World Business Lenders.

He says he has worked with a lot of ISOs and many of them don’t want to pay reps a base salary because they feel it’s a mistake to give them a cushion. Because by doing so, reps get comfortable and when they get comfortable, they don’t push deals—or so the thinking goes. But Ramirez believes this is counterproductive to the rep’s career and the ISO’s sales.

He believes reps should be given a big enough base while they are learning the industry—say for 90 days. Giving them $2,500 a month or so, motivates them and it doesn’t choke their possibility for survival. “You have to give every salesperson the opportunity to succeed. Give them some coaching, give them some guidance, give them a little time. But if there’s no possibility of that rep succeeding or being an asset to your team, it’s important to remove them as efficiently as possible,” he says.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but removing dead weight is also motivating for reps who are really working hard to sell, Ramirez says. To keep that person is demoralizing for the other reps—who may feel they don’t have to work as hard either or who feel they have job security even without doing their best. “It fosters complacency,” he says.

Lend Us An Ear: Women in the Industry Speak Their Mind

August 11, 2016

The majority (52.5 percent) of employees in the banking and insurance industries are women — if this sounds strange, that’s because it is, considering only 1.4 percent eventually go on to become CEOs. While the male dominance is not apparent at the mid-management executive level, the sex ratio is rather skewed on top. Needless to say?

AltFinanceDaily grabbed the opportunity to speak to three women in the alternative business financing industry, charting their journey, reliving their experience, knowledge and the lessons that got them to where they are. Here are excerpts from the interviews.

Back to Roots

For some, their careers are not a deliberate choice, but a serendipitous stumble.

Heather Francis, CEO of Florida-based Elevate Funding, who went to college to become a healthcare professional entered finance by happenstance. “I went to school for health promotion and education at the University of Florida and graduated in 2007,” said Francis, who comes from a family of entrepreneurs and is a fifth generation Floridian. “I found that the position I was looking for was not a necessity for companies, it was a luxury like setting up gyms, that people were not willing to pay for at that time.”

Francis landed her first job in finance with a private equity firm called Strategic Funding in Gainesville, Florida where she set up the firm’s merchant cash advance business. After spending seven years there, in 2014, she set up Elevate Funding which in a short span of 16 months has made over 1,000 advances to businesses.

For Kabbage Loans cofounder Kathryn Petralia too, fintech was a far cry from wanting to be an English professor. A graduate from Furman University, Petralia’s tryst with finance was when she got roped into a project, valuing companies using data compression tools. Riding on building her tech expertise, she founded her first company at 25 which made store catalogues digital. “I was a kid and did not know anything about marketing or sales, so I ended up selling the startup to the company which helped me build it.” The venture however gave her an in into finance and she went on to work for Revolution Money and eventually built Kabbage Loans.

But for Danille Rivelli, VP of Sales at United Capital Source, however, the jump wasn’t as big or unusual. Although finance was not originally on her mind as an art major, it was a natural path from what she began doing to acquire real-world work experience during school, selling mortgages. Rivelli changed her academic focus and went on to get a business degree from Briarcliff College, where she also played on the softball team.

“A year or two into college, I started doing mortgages, making 5 percent commissions. It was natural and it just kinda flowed,” said Rivelli whose first job out of college was on the sales floor at Merchant Cash Capital, now Bizfi. “I wanted to get out of mortgages and I was hooked when I saw the sales floor, it was fun and upbeat.” She was also one of the company’s youngest salespeople at the time.

Women Can Do No Wrong. Or Can They?

When we asked what women need to do differently at workplaces? The answer was quick, resounding and not surprisingly – be more assertive.

“Women think from the heart more than the mind,” said Rivelli. “I find myself in situations sometimes where I know that I should be ‘leaving the emotions out of it’ so that I’m not second-guessing myself as much.” But it’s what helps her build lasting relationships with clients. “I think most effective sales people will agree that the most important part of our job is listening. You want to really know and understand who your client is and what they’re looking for before you try to sell to them.”

According to Petralia, who thinks of herself as ‘one-of-the-guys,’ the problem lies in overplaying the differences between men and women. “I think we perpetuate the stereotype that men are supposed to behave a certain way and women aren’t. I notice that when men crack a joke or use a curse word, they immediately apologize to the women in the room. We are making that happen,” she said. Petralia’s strategy in such scenarios is to swing to the other side and initiate banter. “I am very comfortable with dirty jokes and f-bombs.”

“Men are really good at faking it ’til they make it. They position themselves as experts when they are not but women are unsure of jumping into the deep end when they are not sure they can swim and that’s a big part of what we have to overcome,” Petralia said.

Francis is on the same page, “Men have no problem tooting their horn, but women don’t do that. We cannot expect anyone to stand up for us. If you think you’re getting looked over for a promotion, walk up to your boss and say it,” she said. Francis talks about most of the struggle being personal rather than operational. “I will admit to us having a need to be right… right about decisions, right in arguments and right about where the furniture goes,” she says jokingly. “A lot of what led me to start Elevate was my belief in that you could service the risky credit market without taking advantage or putting insane demands on the performance of the portfolio and still be successful… having that theory validated and accepted and in the end, being right.”

What’s the hurdle, what’s the race?

And the assertiveness comes from one’s belief in their struggle and the value of that struggle. Petralia reminisces of a time when as a scrimping 25-year-old entrepreneur, she pitched a tent and stayed on a campsite in San Francisco while raising money for her startup. Two decades later, she runs a billion dollar lending company. Petralia recognizes that not all women have the same opportunities.

“When I was raising money for Kabbage, I realized that I had only been in one or two meetings where a woman wasn’t bringing me water,” said Petralia who believes that bringing diversity requires work and companies should set targets and find qualified diverse candidates.

Kabbage allows for 12 weeks of maternity leave but that pales in comparison with other countries, says Petralia. “The problem with women is, we have the babies. Women have to choose between their careers and personal life and we are not even close to making that situation better. The key time in their 30s when they are having kids, they come back to compete with younger people who are cheaper.”

The movement to make it better, according to her should begin with creating a system of incentives like better child care, easy commute to work etc. where women don’t have to choose between advancing their career and having a child.

And her other gripe is limp handshakes from men. “Shake women’s hands better. Men give this limp, deadfish like handshake at conferences to women and it’s the worst.”

According to Francis, equal footing comes from striving for professional equality and representation. She says being a woman opens many doors but that’s where it stops. “People will talk to you nicely if you’re a woman but they don’t think you are the person making the decision. You have the ability to start the conversation but no one thinks that you can finish it.”

And for Rivelli, that means giving it your all. “The point is to keep being so good that no one can ignore you,” she said.

Stairway to Heaven: Can Alternative Finance Keep Making Dreams Come True?

April 28, 2016

The alternative small-business finance industry has exploded into a $10 billion business and may not stop growing until it reaches $50 billion or even $100 billion in annual financing, depending upon who’s making the projection. Along the way, it’s provided a vehicle for ambitious, hard-working and talented entrepreneurs to lift themselves to affluence.

Consider the saga of William Ramos, whose persistence as a cold caller helped him overcome homelessness and earn the cash to buy a Ferrari. Then there’s the journey of Jared Weitz, once a 20 something plumber and now CEO of a company with more than $100 million a year in deal flow.

Their careers are only the beginning of the success stories. Jared Feldman and Dan Smith, for example, were in their 20s when they started an alt finance company at the height of the financial crisis. They went on to sell part of their firm to Palladium Equity Partners after placing more than $400 million in lifetime deals.

Their careers are only the beginning of the success stories. Jared Feldman and Dan Smith, for example, were in their 20s when they started an alt finance company at the height of the financial crisis. They went on to sell part of their firm to Palladium Equity Partners after placing more than $400 million in lifetime deals.

The industry’s top salespeople can even breathe new life into seemingly dead leads. Take the case of Juan Monegro, who was in his 20s when he left his job in Verizon customer service and began pounding the phones to promote merchant cash advances. Working at first with stale leads, Monegro was soon placing $47 million in advances annually.

The industry’s top salespeople can even breathe new life into seemingly dead leads. Take the case of Juan Monegro, who was in his 20s when he left his job in Verizon customer service and began pounding the phones to promote merchant cash advances. Working at first with stale leads, Monegro was soon placing $47 million in advances annually.

Alternative funding can provide a second chance, too. When Isaac Stern’s bakery went out of business, he took a job telemarketing merchant cash advances and went on to launch a firm that now places more than $1 billion in funding annually.

All of those industry players are leaving their marks on a business that got its start at the dawn of the new century. Long-time participants in the market credit Barbara Johnson with hatching the idea of the merchant cash advance in 1998 when she needed to raise capital for a daycare center. She and her husband, Gary Johnson, started the company that became CAN Capital. The firm also reportedly developed the first platform to split credit card receipts between merchants and funders.

BIRTH OF AN INDUSTRY

Competitors soon followed the trail those pioneers blazed, and the industry began growing prodigiously. “There was a ton of credit out there for people who wanted to get into the business,” recalled David Goldin, who’s CEO of Capify and serves as president of the Small Business Finance Association, one of the industry’s trade groups.

Competitors soon followed the trail those pioneers blazed, and the industry began growing prodigiously. “There was a ton of credit out there for people who wanted to get into the business,” recalled David Goldin, who’s CEO of Capify and serves as president of the Small Business Finance Association, one of the industry’s trade groups.

Many of the early entrants came from the world of finance or from the credit card processing business, said Stephen Sheinbaum, founder of Bizfi. Virtually all of the early business came from splitting card receipts, a practice that now accounts for just 10 percent of volume, he noted.

At first, brokers, funders and their channel partners spent a lot of time explaining advances to merchants who had never heard of them, Goldin said. Competition wasn’t that tough because of the uncrowded “greenfield” nature of the business, industry veterans agreed.

Some of the initial funding came from the funders’ own pockets or from the savings accounts of their elderly uncles. “I’ve met more than a few who had $2 million to $5 million worth of loans from friends and family in order to fund the advances to the merchants,” observed Joel Magerman, CEO of Bryant Park Capital, which places capital in the industry. “It was a small, entrepreneurial effort,” Andrea Petro, executive vice president and division manager of lender finance for Wells Fargo Capital Finance, said of the early days. “A number of these companies started with maybe $100,000 that they would experiment with. They would make 10 loans of $10,000 and collect them in 90 days.”

That business model was working, but merchant cash advances suffered from a bad reputation in the early days, Goldin said. Some players were charging hefty fees and pushing merchants into financial jeopardy by providing more funding than they could pay back comfortably. The public even took a dim view of reputable funders because most consumers didn’t understand that the risk of offering advances justified charging more for them than other types of financing, according to Goldin.

Then the dam broke. The economy crashed as the Great Recession pushed much of the world to the brink of financial disaster. “Everybody lost their credit line and default rates spiked,” noted Isaac Stern, CEO of Fundry, Yellowstone Capital and Green Capital. “There was almost nobody left in the business.”

RAVAGED BY RECESSION

Perhaps 80 percent of the nation’s alternative funding companies went out of business in the downturn, said Magerman. Those firms probably represented about 50 percent of the alternative funding industry’s dollar volume, he added. “There was a culling of the herd,” he said of the companies that failed.

Life became tough for the survivors, too. Among companies that stayed afloat, credit losses typically tripled, according to Petro. That’s severe but much better than companies that failed because their credit losses quintupled, she said.

Who kept the doors open? The firms that survived tended to share some characteristics, said Robert Cook, a partner at Hudson Cook LLP, a law office that specializes in alternative funding. “Some of the companies were self-funding at that time,” he said of those days. “Some had lines of credit that were established prior to the recession, and because their business stayed healthy they were able to retain those lines of credit.”

The survivors also understood risk and had strong, automated reporting systems to track daily repayment, Petro said. For the most part, those companies emerged stronger, wiser and more prosperous when the crisis wound down, she noted. “The legacy of the Great Recession was that survivors became even more knowledgeable through what I would call that ‘high-stress testing period of losses,’” she said.

ROAD TO RECOVERY

The survivors of the recession were ready to capitalize on the convergence of several factors favorable to the industry in about 2009. Taking advantages of those changes in the industry helped form a perfect storm of industry growth as the recession was ending.

The survivors of the recession were ready to capitalize on the convergence of several factors favorable to the industry in about 2009. Taking advantages of those changes in the industry helped form a perfect storm of industry growth as the recession was ending.

They included making good use of the quick churn that characterizes the merchant cash advance business, Petro noted. The industry’s better operators had been able to amass voluminous data on the industry because of its short cycles. While a provider of auto loans might have to wait five years to study company results, she said, alternative funders could compile intelligence from four advances within the space of a year.

That data found a home in the industry around the time the recession was ending because funders were beginning to purchase or develop the algorithms that are continuing to increase the automation of the underwriting process, said Jared Weitz, CEO of United Capital Source LLC. As early as 2006, OnDeck became one of the first to rely on digital underwriting, and the practice became mainstream by 2009 or so, he said.

Just as the technology was becoming widespread, capital began returning to the market. Wealthy investors were pulling their funds out of real estate and needed somewhere to invest it, accounting for part of the influx of capital, Weitz said.

At the same time, Wall Street began to take notice of the industry as a place to position capital for growth, and companies that had been focused on consumer lending came to see alternative finance as a good investment, Cook said.

For a long while, banks had shied away from the market because the individual deals seem small to them. A merchant cash advance offers funders a hundredth of the size and profits of a bank’s typical small-business loan but requires a tenth of the underwriting effort, said David O’Connell, a senior analyst on Aite Group’s Wholesale Banking team.

The prospect of providing funds became even less attractive for banks. The recession had spawned the Dodd-Frank Financial Regulatory Reform Bill and Basel III, which had the unintended effect of keeping banks out of the market by barring them from endeavors where they’re inexperienced, Magerman said. With most banks more distant from the business than ever, brokers and funders can keep the industry to themselves, sources acknowledged.

At about the same time, the SBFA succeeded in burnishing the industry’s image by explaining the economic realities to the press, in Goldin’s view.The idea that higher risk requires bigger fees was beginning to sink in to the public’s psyche, he maintained.

Meanwhile, loans started to join merchant cash advances in the product mix. Many players began to offer loans after they received California finance lenders licenses, Cook recalled. They had obtained the licenses to ward off class-action lawsuits, he said and were switching from sharing card receipts to scheduled direct debits of merchants’ bank accounts.

As those advantages – including algorithms, ready cash, a better image and the option of offering loans – became apparent, responsible funders used them to help change the face of the industry. They began to make deals with more credit-worthy merchants by offering lower fees, more time to repay and improved customer service. “The recession wound up differentiating us in the best possible way,” Bizfi’s Sheinbaum said of the changes.

His company found more-upscale customers by concentrating on industries that weren’t hit too hard by the recession. “With real estate crashing, people were not refurbishing their homes or putting in new flooring,” he noted.

Today, the booming alternative finance industry is engendering success stories and attracting the nation’s attention. The increased awareness is prompting more companies to wade into the fray, and could bring some change.

WHAT LIES AHEAD

One variety of change that might lie ahead could come with the purchase of a major funding company by a big bank in the next couple of years, Bryant Park Capital’s Magerman predicted. A bank could sidestep regulation, he suggested, by maintaining that the credit card business and small business loans made through bank branches had provided the banks with the experience necessary to succeed.

Smaller players are paying attention to the industry, too, with varying degrees of success. Predictably, some of the new players are operating too aggressively and could find themselves headed for a fall. “Anybody can fund deals – the talent lies in collecting the money back at a profitable level,” said Capify’s Goldin. “There’s going to be a shakeout. I can feel it.”

Smaller players are paying attention to the industry, too, with varying degrees of success. Predictably, some of the new players are operating too aggressively and could find themselves headed for a fall. “Anybody can fund deals – the talent lies in collecting the money back at a profitable level,” said Capify’s Goldin. “There’s going to be a shakeout. I can feel it.”

Some of today’s alternative lenders don’t have the skill and technology to ward off bad deals and could thus find themselves in trouble if recession strikes, warned Aite Group’s O’Connell. “Let’s be careful of falling into the trap of ‘This time is different,’” he said. “I see a lot of sub-prime debt there.”

Don’t expect miracles, cautioned Petro. “I believe there will be another recession, and I believe that there will be a winnowing of (alternative finance) businesses,” she said. “There will be far fewer after the next recession than exist today.”

A recession would spell trouble, Magerman agreed, even though demand for loans and advances would increase in an atmosphere of financial hardship. Asked about industry optimists who view the business as nearly recession-proof, he didn’t hold back. “Don’t believe them,” he warned. “Just because somebody needs capital doesn’t mean they should get capital.”

Further complicating matters, increased regulatory scrutiny could be lurking just beyond the horizon, Petro predicted. She provided histories of what regulation has done to other industries as an indication of the differing outcomes of regulation – one good, one debatable and one bad.

Good: The timeshare business benefitted from regulation because the rules boosted the public’s trust.

Debatable: The cost of complying with regulations changed the rent-to-own business from an entrepreneurial endeavor to an environment where only big corporations could prosper.

Bad: Regulation appears likely to alter the payday lending business drastically and could even bring it to an end, she said.

Still, regulation’s good side seems likely to prevail in the alternative finance business, eliminating the players who charge high fees or collect bloated commissions, according to Weitz. “I think it could only benefit the industry,” he said. “It’ll knock out the bad guys.”

Google Culls Online Lenders – Pay or Else?

March 15, 2016Can you become one of the biggest or most successful online lenders without Google? A search layout update may be inadvertently culling the herd.

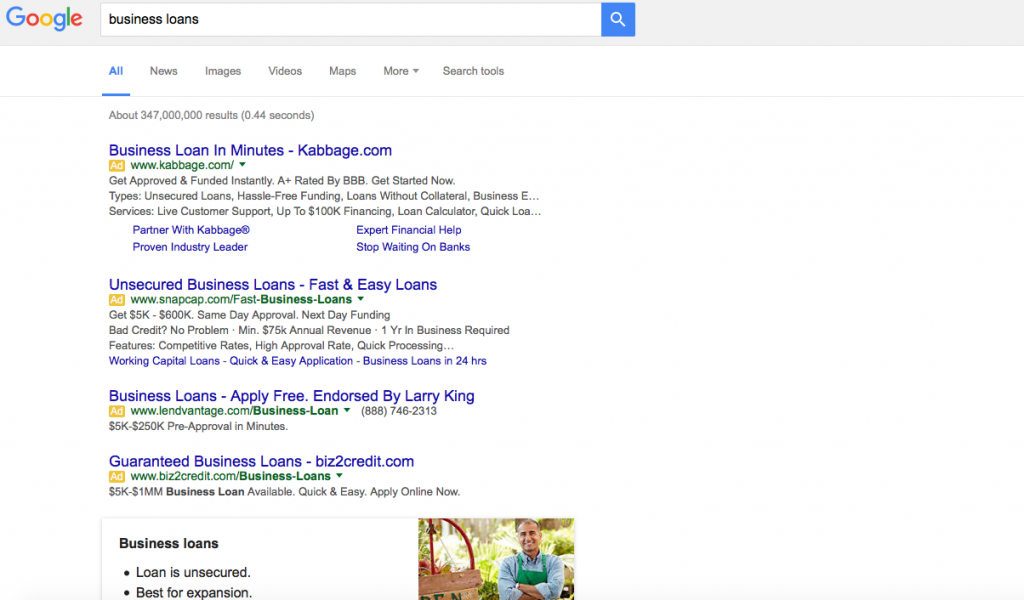

In late February, Google eliminated ads from the right side of the page while adding another layer to the top and bottom. When factoring in features like site links, the effects on organic search has been devastating. Non-paid links are now entirely below the fold for many commercial keywords, which means users may limit their selections entirely to ads. Here’s an example of a full screen browser window on a Macbook Air when searching for Business Loans:

Brad Geddes, a Google Adwords marketing author, expert and consultant, has said the Click-through rate (CTR) on this new 4th ad placement is skyrocketing. “Depending on the keyword, position 4 is going to have a 400%-1000% CTR increase,” he said on Webmaster world. And while side links and bottom links were never a huge factor anyway (less than 15% of click-throughs), Geddes believes a consequence of this change is that fewer ad slots means higher cost bids to rank on the 1st page. “Companies with thin margins are going to have a lot of words fall to page 2,” he wrote.

In summary: Fewer ad placements, higher costs per click, decreased likelihood of organic click-throughs.

And the online lending industry is already feeling the burn. Several funders and ISOs on the commercial side have told AltFinanceDaily in confidence that the online lead gen battle has been lost or that they have been temporarily sidelined by the increase in costs. At least one funder is refocusing their efforts entirely on the ISO channel after a horrible experience with Pay-Per-Click.

And it’s not just the costs, it’s the quality of leads, they say. The searchers clicking their expensive ads and running up their bills sometimes literally meet none of the qualifications their ads stipulate. Yet many searchers click anyway, rendering the ads’ carefully scripted messages moot. One study might explain why that is. In it, users spent around .764 seconds considering the first paid search result and a total of only 4.5 seconds scanning the first five results. That’s not a whole lot of time to read each ad, digest them and consider whether or not there’s an appropriate fit.

And it’s not just the costs, it’s the quality of leads, they say. The searchers clicking their expensive ads and running up their bills sometimes literally meet none of the qualifications their ads stipulate. Yet many searchers click anyway, rendering the ads’ carefully scripted messages moot. One study might explain why that is. In it, users spent around .764 seconds considering the first paid search result and a total of only 4.5 seconds scanning the first five results. That’s not a whole lot of time to read each ad, digest them and consider whether or not there’s an appropriate fit.

On one industry forum, ISOs have reported that the cost of acquiring a merchant cash advance or business loan deal from Pay-Per-Click is ranging from $700 to $1,200. “PPC for premium keywords as high as $40 at times. Ugly. Real ugly,” one user wrote. Another user wrote, “It’s not just Adwords that is saturated. The whole market is saturated. Lenders and the onslaught of new brokers are making it tough. Lenders with programs like Funding Circle and Kabbage, and with all the advertising money in the world to burn and get direct traffic.” And still another believes that online ads are simply inviting the lowest hanging fruit. “Internet leads have the highest level of fraud,” said one sales manager.

Notably, many of the top 8 funders are only competing for a limited number of competitive keywords or may not even be running Adwords at all. PayPal and Square for example, focus only on their existing payment processing customers despite being “online lenders.”

It’s too early to tell what effects Google’s ad changes will have on the online lending industry, though a couple of companies who were paying just enough to extract clicks from side ads have indicated the change is for the worse and they have suspended their campaigns.

The natural alternative to paid search, organic search, is seldom discussed anymore as a realistic strategy these days, in part because the rankings might be rigged anyway.

One irony that’s pervasive in the online lending industry is that borrowers are being targeted offline where it’s potentially more affordable. In a discussion thread that garnered 76 posts last fall, ISOs and funders suggested that direct mail, referrals, UCCs, cold calling, radio and even going out and shaking hands, were pegged as “what’s next” for marketing. Pay-Per-Click was only mentioned once and only in the context of it being something that had long ago been made too expensive for small and mid-size companies.

The cost of making these things work might be why so many funders are hoping that brokers can figure it out. “We decided that the best way to grow is to build relationships to avoid the overhead, compliance, training and manpower that a sales team would require,” said Nulook Capital’s Jordan Feinstein in an interview with AltFinanceDaily last month.

With Google becoming even more competitive now though, perhaps United Capital Source’s Jared Weitz summed it up best. “Marketing is getting more expensive and only the ones who can afford to pay can play,” Weitz said.