Lending Club Stock Curiously Clobbered

January 20, 2016When Lending Club’s share price was nearing its all-time lows late last year, one might think that company executives would be eager to buy, if for no other reason than to signal long-term confidence. That’s precisely what company CEO Renaud Laplanche did when he bought 60,000 shares on November 30th. And from that date until December 10th, the stock rose from $12.02 to $14.16. That put them within a dollar of their $15 IPO price, a reassuring sign even if they were still down 50% from their all-time high a year earlier.

Here’s what happened next:

- December 14th: The company’s Chief Financial Officer sold 13,950 shares

- December 15th: Board member and former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers sold 23,421 shares.

- December 16th: The Fed raised interest rates

- December 18th: The company’s Chief Risk Officer sold 75,000 shares. (stock closed at a new all-time low of $11.48)

- January 6th: The company’s Chief Marketing/Operating Officer sold 35,000 shares. (stock closed at a new all-time low of $10.12

- January 11th: The company’s Chief Technology Officer sold 12,500 shares. (stock closed at a new all-time low of $9.24)

- January 12th: The company’s Chief Technology Officer sold 12,500 shares.

- January 13th: The company’s Chief Technology Officer sold 12,500 shares. (stock closed at a new all-time low of $8.86)

- January 14th: The company’s Chief Technology Officer sold 12,500 shares. (stock closed at a new all-time low of $8.02)

While company insiders were selling relatively small blocks of shares and likely doing it to bank just a little bit of their paper wealth, the trades coincided with the company’s plunge to oblivion and perhaps contributed to the drop in the first place. On January 14th, the date of the last insider sale, trading volume spiked to nearly 5x the daily average and the share price hit a record intraday low of $7.76.

While company insiders were selling relatively small blocks of shares and likely doing it to bank just a little bit of their paper wealth, the trades coincided with the company’s plunge to oblivion and perhaps contributed to the drop in the first place. On January 14th, the date of the last insider sale, trading volume spiked to nearly 5x the daily average and the share price hit a record intraday low of $7.76.

Lending Club finished at $7.34 on January 19th, a new all-time record low, with dips as low as $7.05 intraday. That means the stock has dropped nearly 40% since the CEO bought shares less than two months ago. By comparison, the S&P 500 is down 9.5% over that time period.

The share price death spiral has arguably made it easier to spread fear. In the Lending Club subforum on the LendAcademy website for example, a user claiming to manage a hedge fund urged members who use Lending Club’s marketplace to sell everything now and prepare for an armageddon of loan defaults. That thread was suspiciously created around the market open of January 14th, the date with the most trading volume since the IPO.

Meanwhile investors in Lending Club’s notes have remain largely unperturbed. And why wouldn’t they? They’re still enjoying very attractive returns and despite all the doom and gloom, everything is pretty much business as usual.

In a note to shareholders, Compass Point Research and Trading, LLC set a price target of $12 for Lending Club back in December on the risk of the Madden v. Midland case, Congressional investigations into terrorism finance, and the California Department of Business Oversight inquiry into marketplace lenders. While all are perhaps concerning, none seem to present an immediate threat. The most likely reason for the run on Lending Club is that general market fear is stoking reminders of the 2008 crash in which anything related to lending was toxic. As of Tuesday’s close, OnDeck, a business lender often compared to Lending Club, was down 61% from their IPO price. Lending Tree, an online consumer lending portal was down 51% from its 52 week high.

Meanwhile, Lending Club posted positive results in the 3rd quarter. Compared to the same period last year, revenue more than doubled, adjusted EBITDA tripled, and loan originations doubled. They also posted a profit. Overall, these results should not have caused the stock to drop by 50% over the next few months.

As a marketplace, Lending Club does not keep the loans it makes on its balance sheet. That’s something a lot of investors might be overlooking. They may have been clobbered these last few months but the fears might be somewhat unfounded. ..

Year of The Broker Concludes – 2015 Recap

December 31, 2015 It was the Year of the Broker, a phrase that often conjured up images of easy money and inexperience. Lenders like OnDeck reacted by reducing their dependence on them. Responsible for 68.5% of their deal flow in 2012, OnDeck only sourced 18.6% of their deals from brokers in the third quarter of 2015.

It was the Year of the Broker, a phrase that often conjured up images of easy money and inexperience. Lenders like OnDeck reacted by reducing their dependence on them. Responsible for 68.5% of their deal flow in 2012, OnDeck only sourced 18.6% of their deals from brokers in the third quarter of 2015.

But there’s money being made. One broker is on pace to do more than $100 million worth of deals annually after working as a plumber eight years ago. Another went from sleeping in his car to driving a Ferrari. Meanwhile, brokers like John Tucker are basically saying just the opposite. Tucker has repeatedly taken to AltFinanceDaily to preach things like “minimalism,” a practice of living below your means to a point where you can survive, and telling everyone it’s okay to embrace the satisfaction of a middle class life.

So is it the end of days or just the beginning?

In October, initial survey results of top industry CEOs revealed a confidence index of 83.7 out of 100, but out there on the street for the little guy, it’s been a tumultuous year. Things like commission chargebacks have hit brokers at unexpected times, with several funders privately telling us over the year that rogue brokers have closed their bank accounts or frozen the ACH debits in order to avoid giving the commissions back.

In 2015, brokers sued their sales agents and sales agents sued their employing brokers. Deals got backdoored, deals got co-brokered, and soliciting deals anonymously got banned from industry forums. Stacking continued mostly unfettered but is being pursued in the court system by funders allegedly injured by it. Brokers took over Wall Street and are supposedly being watched by regulators. Oh, and robo-dialing? Brokers should probably steer clear of that, just as underwriters should ditch paper bank statements.

It’s a lot to manage. Sometimes for a broker, just losing a deal can make them so sick that they have to go home. That’s apparently what happens when you don’t answer the phone fast enough. At least one said there’s no room left for more competitors so if you were thinking of starting a brokerage now, $2,000 won’t be enough.

But things could be worse. In 2015, IOU Financial was under attack by Russian nuclear scientists, a story that was more truth than exaggeration. In the end, Qwave Capital acquired a 15% stake in IOU.

An OnDeck class action lawsuit that looked bad at first turned out to be mostly based on the words of a convicted stock manipulator with a short position in the stock. The case is still ongoing and OnDeck’s stock price is down 50% from their IPO.

In 2015, two guys lost God but found $40 million (although numerous sources say that number is off).

“Madden” no longer means the football video game and Section 1071 is not a seating area in a stadium.

An RFI turned out to be something not to LOL about. Despite an overwhelming response from lenders and funders, the Treasury isn’t completely sold.

Things weren’t so automated in 2015 despite the cries of technological disruption. Maybe that’s why it feels like 1997. Manual underwriting still dominated and bank statements still matter as much as they ever did. God declined loan applications, Google rigged the search results, and a mayor declared war on merchant cash advance (and then never spoke about it ever again after being re-elected).

Things weren’t so automated in 2015 despite the cries of technological disruption. Maybe that’s why it feels like 1997. Manual underwriting still dominated and bank statements still matter as much as they ever did. God declined loan applications, Google rigged the search results, and a mayor declared war on merchant cash advance (and then never spoke about it ever again after being re-elected).

Lobbying coalitions formed. NAMAA became the SBFA. The CFPB lied and community bankers testified.

But things are looking up. Brokers can obtain outside investments, get acquired, or make millions through syndication.

Bad Merchants are now ending up in more than one bad database, though a deal for the ages slipped through the cracks. Other merchants went to jail. Square went public and brought merchant cash advances along with them. The industry beamed its message through Times Square and one Democratic congressman has asked God to bless it all.

It was a crazy year. Marketplace lending became an acknowledged term (and the name of a conference) and already companies under that umbrella have been linked to presidential candidate (and desperate loser) Jeb Bush and the San Bernardino Terrorists. The FDIC had a few things to say and SoFi went triple-A. Marketplace lending is making a lot of people money, but when looking at the tax implications is there something funny?

In 2015, the big boys shared their wisdom and their figures. Turns out, it was beyond hyperbole. Brokers experienced an incredible rise or they pawned their ferrari to the other guys. Some focused on a specific crop, while others are trying it over the top. California sucked, John Tucker tucked, and one lender got totally F*****. In 2015 some funders got tanked, so in 2016 we’ll all be AltFinanceDaily.

Happy New Year!

Merchant Cash Advance is The Real Square IPO Story

November 22, 2015 Square’s debut on the New York Stock Exchange is being talked about as one of the more consequential IPOs of 2015. As a mobile payments company famous for both losing money and its founding by Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, the $2.9 billion valuation pales in comparison to its rival First Data that went public just a month before. First Data, which was founded in 1971, is worth five times more than Square with a market cap of $14.7 billion to Square’s $2.9 billion. But it’s Square that everyone’s talking about and not necessarily in a positive way. Cast as the poster child for runaway private market valuations in Fintech, Square’s Series E round just a year before had supposedly increased its worth to $6 billion.

Square’s debut on the New York Stock Exchange is being talked about as one of the more consequential IPOs of 2015. As a mobile payments company famous for both losing money and its founding by Jack Dorsey, Twitter’s CEO, the $2.9 billion valuation pales in comparison to its rival First Data that went public just a month before. First Data, which was founded in 1971, is worth five times more than Square with a market cap of $14.7 billion to Square’s $2.9 billion. But it’s Square that everyone’s talking about and not necessarily in a positive way. Cast as the poster child for runaway private market valuations in Fintech, Square’s Series E round just a year before had supposedly increased its worth to $6 billion.

Robert Greifeld, the CEO of Nasdaq, had warned people just weeks earlier about the validity of private market valuations. “A unicorn valuation in private markets could be from just two people,” he said. “Whereas public markets could be 200,000 people.”

And while Square’s IPO was relatively well-received, closing at 45% above its offered price, there’s an entire story beyond payments hidden in the company’s financial statements under the label of “software and data products.” That’s code for merchant cash advance, the working capital product they offer to customers that currently makes up 4% of the company’s revenue.

“Since Square Capital is not a loan, there is no interest rate,” states the company’s FAQ. That echoes what dozens of other merchant cash advance companies have been saying for a decade. “You sell a specific amount of your future receivables to Square, and in return you get a lump sum for the sale,” marketing materials explain.

Lenders that don’t approve of this receivable purchase model are lobbying politically against it, some of whom are well-known. Lending Club for example, is a signatory to the Responsible Business Lending Coalition’s Small Business Borrowers Bill of Rights (SBBOR), committing themselves to things like transparency and the disclosure of APRs even for non-loan products.

But disclosing an APR on a receivable purchase merchant cash advance transaction is not only impossible since there is no time variable, but would violate the spirit of the contract even if estimates were used to fill in the blanks. Nonetheless, Fundera CEO Jared Hecht, whose marketplace platform has also signed the SBBOR told Forbes in September that “small business owners have been sold by pushy salespeople, hiding terms, disguising rates and manipulating customers into taking products that aren’t good for them.”

But disclosing an APR on a receivable purchase merchant cash advance transaction is not only impossible since there is no time variable, but would violate the spirit of the contract even if estimates were used to fill in the blanks. Nonetheless, Fundera CEO Jared Hecht, whose marketplace platform has also signed the SBBOR told Forbes in September that “small business owners have been sold by pushy salespeople, hiding terms, disguising rates and manipulating customers into taking products that aren’t good for them.”

Ironically, Fundera’s own merchant cash advance partners have not made any such pledge to disclose APRs. No one’s commitment is verified anyway. “Neither Small Business Majority nor any other coalition member independently verifies that any of these signatory companies or entities in fact abide by the SBBOR,” the group’s website states. This isn’t to say that their intent is misguided, there’s just very little substance to it below the surface.

For example, while the coalition has made some subtle and not so subtle digs about merchant cash advances over fairness and transparency, it’s the lending model used by some of the SBBOR’s signatories that is being challenged by the courts right now. Because of Madden v. Midland, Lending Club’s practice of using a chartered bank to originate loans could potentially be in jeopardy. The ruling was just appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. At the heart of the issue is the ability to usurp state usury caps through the National Bank Act. For a company that has pledged to offer non-abusive products, it’s ironic that their model relies on preemption of state interest rate caps all the while reassuring their shareholders that there’s no risk because of their Choice of Law fallback provision. In truth, Lending Club uses a state chartered bank and not a nationally chartered bank and thus would be somewhat shielded in an unfavorable Supreme Court ruling.

Those concerned in years past that receivable purchase merchant cash advances were full of regulatory uncertainty had shifted towards the model that Lending Club uses since it was perceived to have more nationally recognized legitimacy. However, with that model seriously challenged, old school merchant cash advances are once again looking pretty good. That’s probably why publicly traded Enova International Inc. (NYSE:ENVA) bought The Business Backer this past summer. And it’s why Square skated through their IPO without much resistance to their merchant cash advance activities.

The story of Square was either that it was overvalued, that CEO Jack Dorsey couldn’t handle running two companies, that they were losing money, or that their deal with Starbucks was a mistake. Meanwhile Square has processed $300 million worth of merchant cash advances, a product that doesn’t disclose an APR since it’s not a loan. “Nearly 90% of sellers who have been offered a second Square Capital advance cho[se] to accept a repeat advance,” their S-1 stated.

“If our Square Capital program shifts from an MCA model to a loan model, state and federal rules concerning lending could become applicable,” it adds. And right now partly due to Madden v. Midland, the loan model looks pretty shaky. Square proved many things when they went public on November 19th and one was that merchant cash advances are just the opposite of what critics have argued in the past.

Battery Ventures’ general partner Roger Lee told Business Insider, “the [Square Capital] product itself will have unique advantages in the market, and it’s a big market.”

Listen to OnDeck’s Q3 Earnings Call

November 1, 2015 Anyone can listen in to OnDeck’s Q3 Earnings call on Monday, November 2nd by dialing into (877) 201-0168 and using conference ID 55963420.

Anyone can listen in to OnDeck’s Q3 Earnings call on Monday, November 2nd by dialing into (877) 201-0168 and using conference ID 55963420.

OnDeck closed sunday at $9.52 and has been relatively stable since August 6th, but has not been able to gain any ground back toward its IPO price of $20.

In their Q2 earnings call, the company admitted that they were up against competition in the direct mail channel. CEO Noah Breslow argued their strategy was to “break through the clutter” and “better communicate our value proposition.” He later added that “competition for customer response remains elevated.”

Back in August, Compass Point analyst Isaac Boltansky wrote to subscribers that the Madden v Midland ruling would hang over the heads of OnDeck and other marketplace lenders.

In an article by Deborah Festa, Robert C. Hora, Douglas Landy and Albert A. Pisa of Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP, they wrote that one thing that could be done is to simply avoid Second Circuit jurisdiction. “Madden is directly binding if a defendant to a usury claim is sued in and subject to personal jurisdiction in the Second Circuit,” they wrote. “Excluding loans to borrowers located in the Second Circuit may reduce the risk of a usury lawsuit being filed in that circuit,” but added that it wasn’t a foolproof fix.

Meanwhile, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP attorney Brian Korn said at an invite-only event hosted by Herio Capital on October 8th, that the Madden v. Midland ruling was a non-event for business lenders.

And in Lending Club’s Q3 earnings report, they said, “In regards to our loan issuance framework, we continue to see no measurable impact from the Madden decision that was rendered in May this year by the second circuit Court of Appeals.”

OnDeck is therefore likely to be evaluated on their ability to scale originations as well as keep marketing costs and bad debt down. Analysts may also consider whether or not the lender can defend its relatively high costs and collection practices in an age where the mainstream media is scrutinizing alternative lenders with a closer eye.

The company responded to a front-page NY Times article that put them in an unflattering light earlier this month.

For Lending, It Might as Well be 1997

October 9, 2015 If you did any business with OnDeck between 2008 and 2014, you probably spoke with or at least knew of Sherif Hassan. His last position with the company before he left in May, 2014 was the Vice President of Major Markets. About six months later OnDeck went public and Hassan, one of the company’s earliest employees, was not there to celebrate it.

If you did any business with OnDeck between 2008 and 2014, you probably spoke with or at least knew of Sherif Hassan. His last position with the company before he left in May, 2014 was the Vice President of Major Markets. About six months later OnDeck went public and Hassan, one of the company’s earliest employees, was not there to celebrate it.

That’s because Hassan was busy working on something new, Herio Capital, a provider of working capital to small businesses that just recently surpassed more than $10 million in funding since inception.

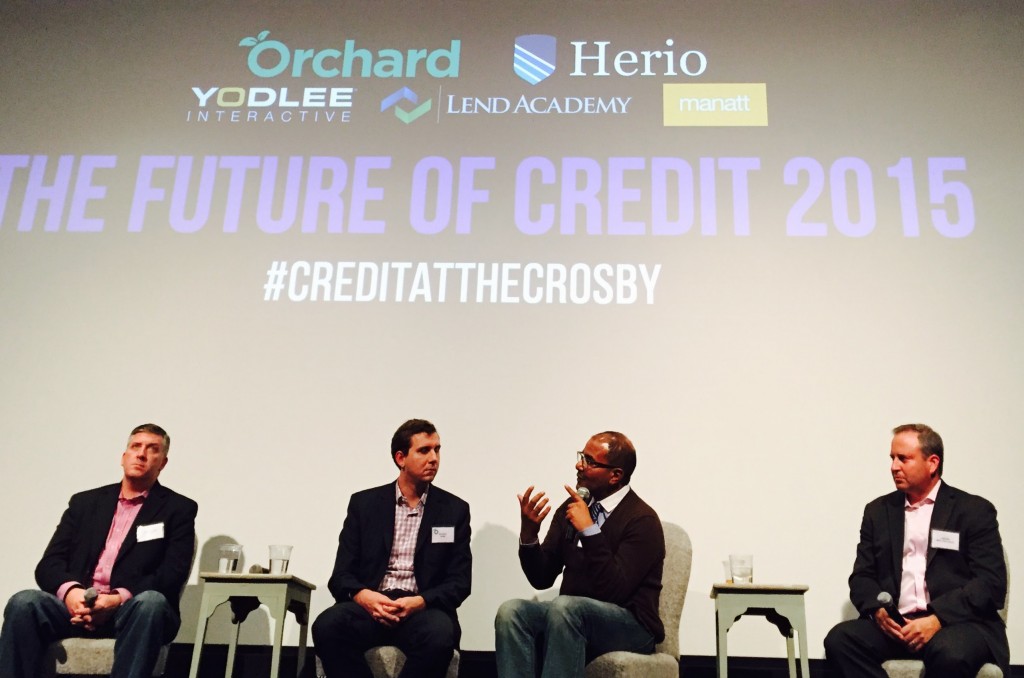

Herio teamed up with Orchard on Thursday evening, September 8th to present The Future of Credit 2015.

“This is e-commerce in 1997 right now for lending,” said Jason Jones, a partner in Lend Academy who moderated the event’s panel. And Hassan, who is now easily considered an industry veteran, explained what set his new company apart.

It’s apparently not all algorithms when it comes to small business either. “We’re using our data to do all the heavy lifting and we’re using our people to do all the thinking,” Hassan said. And while they can take a deal from start to finish in four hours, they still have a human credit committee process. Other industry leaders have reported using similar approaches. “I like eyes on a deal,” said Orion First Financial CEO David Schaefer back in June at the AltLend conference. But for Herio, APIs and data allow the company to do a lot of filtering before anyone even touches the deal. Yodlee’s bank verification product reportedly plays a big role in being able to do that and Terry McKeown, Yodlee’s Data Practice Manager was coincidentally also on the panel.

Next to Hassan sat Matt Burton, the CEO of Orchard Platform, who was previously the 7th employee of Admeld, a company that was acquired by Google in 2011 for $400 million. His co-founder, Angela Ceresnie, is a former VP of Risk Management at Citibank and Director of Risk Management at American Express.

Speaking on the availability of decisioning tools, Burton said “there’s never been a better time to enter the space.” That may seem counter-intuitive since the frenzy of M&A activity and capital raising over the last couple years has had some players worried there’s a bubble brewing, but studies show they may just be filling a growing gap. Small business lending is actually shrinking in the traditional banking sector in part because of Dodd-Frank.

Speaking on the availability of decisioning tools, Burton said “there’s never been a better time to enter the space.” That may seem counter-intuitive since the frenzy of M&A activity and capital raising over the last couple years has had some players worried there’s a bubble brewing, but studies show they may just be filling a growing gap. Small business lending is actually shrinking in the traditional banking sector in part because of Dodd-Frank.

“Community banks are being destroyed,” said Burton. “All the products they used to be able to provide have been taken away.” That’s not just his opinion either. Three weeks ago, the heads of the Independent Community Bankers of America and National Association of Federal Credit Unions offered testimony to the House Small Business Committee that demonstrated the carnage that regulations were having on their industry. During that hearing, Subcommittee Chairman Tom Rice said, “the burdens created by Dodd-Frank are causing many small financial institutions to merge with larger entities or shut their doors completely, resulting in far fewer options where there were already not many options to choose from.”

So today’s online lending industry might seem really big but it’s relatively small when compared to the shoes they’re trying to fill. Case in point, nearly 10% of the 104 companies that responded to the Treasury RFI on marketplace lending attended Herio & Orchard’s three hour event in New York City. That was determined by a quick show of hands from the audience when asked by Manatt Phelps and Phillips attorney Brian Korn. The industry didn’t seem so big all the sudden.

Korn, making a lawyer joke, likened the Treasury RFI to the first discovery request in a lawsuit, but argued the Treasury Department is not really in a position to be the regulator in this space. He believed their motivation came down to, are we doing enough for small business and are we doing enough to protect consumers?

A more serious issue was the Madden v. Midland decision which has put National Bank Act preemption in uncertain legal limbo. For those still unsure what preemption means, Korn offered an example of a 16-year old obtaining a driver’s license in one state and driving to another state where the minimum driving age is 17. The driver can legally export their home state’s minimum driving age and drive in a state where the age limit is higher. It’s that model which is uncertain now thanks to Madden v. Midland, but with interest rates not with drivers’ licenses.

So what’s the Future of Credit as the event was so aptly named? One could argue that whatever the future is, Orchard and Herio will likely have a place in it. The panelists mostly agreed that while some online lenders might be at risk in the next credit cycle, the online lending concept is here to stay. That’s because the borrowers themselves have changed. Nobody’s going to want to walk into a bank anymore and fill out paperwork after this, they argued.

If Lend Academy’s Jason Jones was right about this being like e-commerce in 1997, then it’s certainly incredible to think that the future of credit is something we can hardly even imagine yet.

Stock Slump Makes Marketplace Lending Look Like Safe Haven

September 2, 2015 The premium might be gone in peer-to-peer lending, but a step forward is definitely still better than three steps back. Probably the most frustrating thing for long term investors in the stock market is the day-to-day volatility. Some of it’s rational, and some of it’s just, well, who knows…. it’s the stock market.

The premium might be gone in peer-to-peer lending, but a step forward is definitely still better than three steps back. Probably the most frustrating thing for long term investors in the stock market is the day-to-day volatility. Some of it’s rational, and some of it’s just, well, who knows…. it’s the stock market.

It’s a hopeless feeling to see your stock portfolio balance drop substantially all because something is happening in China. But if you’ve diversified your overall investment portfolio beyond just stocks, it’s not all bad right now. It’s actually a bit of a golden era.

On Lending Club, my portfolio’s Adjusted Net Annualized Return is 8%. On Prosper, my Annualized Return is 11%, though that portfolio is younger and smaller. And then there’s my merchant cash advance portfolio which is beating both of those by a long shot.

These investments are a wonderful balance to the stock market because they don’t care what’s happening in China either. It’s times like these though when you need to be patient and not overreact. The easy mistake to make right now is to substantially reallocate your portfolio so that the majority of your capital is in marketplace loans.

LendingMemo’s Simon Cunningham believes that having 20% of your portfolio in peer-to-peer lending investments is reasonable.

And Lend Academy founder Peter Renton told Equities.com last year that, “The official word from the platforms is that you should not invest more than 10 percent of your net worth.” He also went on to say that some people are putting half their life savings into this and that it’s probably not a good idea.

And he’s right. As volatile as stocks can be, your steep loss today can be erased by a rally tomorrow. With notes backed by the performance of loans, a loss today can’t just rally back tomorrow. When the loans go bad, the money is gone and thus the risk of loss is a little bit more permanent since you can’t just ride it out.

In that same interview, Renton said, “If there were another 2008 or 2009 now, I feel very confident that my returns would remain positive. I’m earning close to 12 percent right now. If there were another 2008-9 right now, I might go down to 6 percent.”

I think that’s probably a best case scenario in a worst case scenario. Everyone should plan for events or contingencies that will lead to losses. If there were no possible outcomes that could lead to losses, then the market has obviously mispriced the loans and I don’t believe that has happened.

One nightmare scenario to consider for example, is if the loans are invalidated by a court. Oddly enough, this very possibility is being discussed after the outcome of the Madden v. Midland ruling which hurt the reliance on chartered banks to originate loans. Lending Club’s CEO answered concerns over that by saying they were protected by their choice of law provision, a safeguard that just recently proved to be imperfect.

As Patrick Siegfried, Esq, wrote, “Last Thursday, the Attorney General of North Carolina was granted an injunction against Western Sky Financial and CashCall prohibiting them from offering any loans to North Carolina consumers or collecting on any outstanding accounts in that state.” The companies pointed to their choice of law provisions that supposedly made the rates permissible. This practice is actually commonplace for alternative lenders. But Siegfried said, “Because the Attorney General was not a party to the agreements, the court found that the Attorney General was not bound by the agreements’ choice of law. Therefore it could enforce North Carolina’s usury laws against the defendants.”

Now however remote the possibility of judicial or regulatory invalidation of loans, it is sobering possibilities like these that should prevent anyone from putting half their life savings into marketplace lending. It is a nice complement to a portfolio of stocks, but not a replacement for one.

Over the last week, my marketplace lending portfolios have been a bright spot and a source of optimism in a news cycle and market that has suddenly turned bearish. I’m tempted to reallocate my investments accordingly, but I’m not going to.

Hopefully you won’t make any impulsive maneuvers either…

Should Alternative Lenders Reconsider IPOs?

August 31, 2015 OnDeck has gotten very quiet over the past month as the stock hovers near its all time low, and down more than 50% from its IPO price. The only updates related to them on the news wire lately are reminders from law firms to join in on the existing class action lawsuit. One has to wonder if they regret going public.

OnDeck has gotten very quiet over the past month as the stock hovers near its all time low, and down more than 50% from its IPO price. The only updates related to them on the news wire lately are reminders from law firms to join in on the existing class action lawsuit. One has to wonder if they regret going public.

To make the things murkier, the Madden v. Midland decision effectively makes it illegal in a handful of states for alternative lenders to rely on chartered banks to originate loans for them at interest rates that violate state usury laws. In states such as New York, that’s a big problem for OnDeck, but fortunately for them and other lenders like them, they can still fall back on a choice of law provision to still be able to make the loans.

Combine that landmark ruling with the Treasury RFI, The Dodd Frank Section 1071 Reg B rule that everyone wants enforced all of the sudden, and a chorus of lenders calling for regulatory action, and we don’t exactly have an ideal environment for other alternative lenders considering an IPO.

But does an IPO really matter?

I am reminded of a long email that Elon Musk sent to employees of SpaceX two years ago regarding their aspirations to go public so that they could monetize their stock options and get rich.

“Some at SpaceX who have not been through a public company experience may think that being public is desirable. This is not so.”

“Another thing that happens to public companies is that you become a target of the trial lawyers who create a class action lawsuit by getting someone to buy a few hundred shares and then pretending to sue the company on behalf of all investors for any drop in the stock price.”

“Public companies are judged on quarterly performance. Just because some companies are doing well, doesn’t mean that all would. Both of those companies (Tesla in particular) had great first quarter results. SpaceX did not. In fact, financially speaking, we had an awful first quarter. If we were public, the short sellers would be hitting us over the head with a large stick.”

“Public company stocks, particularly if big step changes in technology are involved, go through extreme volatility, both for reasons of internal execution and for reasons that have nothing to do with anything except the economy. This causes people to be distracted by the manic-depressive nature of the stock instead of creating great products.”

“It is important to emphasize that Tesla and SolarCity are public because they didn’t have any choice. Their private capital structure was becoming unwieldy and they needed to raise a lot of equity capital.”

“Those rules, referred to as Sarbanes-Oxley, essentially result in a tax being levied on company execution by requiring detailed reporting right down to how your meal is expensed during travel and you can be penalized even for minor mistakes.”

Any other alternative lenders possibly considering an IPO should strongly evaluate whether or not it’s necessary to go public to carry out their objectives. Surely the folks at OnDeck must be at least a little bit distracted by the manic-depressive nature of their stock price, the class action lawsuit, reactions to their quarterly reports, and the unyielding scrutiny by analysts and pundits. Surely it could be argued that they’ve lost some of their PR mojo in the mix.

It’s not easy running a public company, especially a lender in a post-financial crisis world where Wall Street hatred still runs hot. Hopefully if you are in this industry, you are in it for the long haul and not just for an IPO to cash out and give up…

Alternative Lending Becoming Less Alternative

August 23, 2015 Alternative funders are looking a little more like bankers these days, but that’s not to say they’re developing a taste for pinstriped three-piece suits and pocket watches on gold chains. They’re promoting bank loans, applying for California lending licenses and contemplating the unlikely possibility that one day they’ll obtain their own bank charters.

Alternative funders are looking a little more like bankers these days, but that’s not to say they’re developing a taste for pinstriped three-piece suits and pocket watches on gold chains. They’re promoting bank loans, applying for California lending licenses and contemplating the unlikely possibility that one day they’ll obtain their own bank charters.

“It’s what everybody’s talking about,” said Isaac Stern, CEO of Yellowstone Capital LLC, a New York- based funder. “If it’s not in their current plans, it’s in their longer-term plans over the next three to five years.”

Funders promote bank loans to drive down the cost of capital, sell a wider variety of products, offer longer terms and bask in the prestige of a bank’s approval, said Jared Weitz, CEO of United Capital Source.

Loans allow for much more customization than is possible with merchant cash advances, noted Glenn Goldman, CEO of Credibly, which was called RetailCapital until a little less than a year ago. The name changed as the company began offering loans in addition to it original advance business. It’s now working with three banks.

While the terms don’t vary much with advances, borrowers can pay back loans daily, weekly, semi-monthly or monthly, Goldman said. Loans can also include lines of credit that borrowers draw down only when they choose. Interest rates on loans can vary, too, he said, and loans can come due after differing periods of time.

Besides that flexibility, loans also offer familiarity among merchants and sales partners – unlike the sometimes baffling advances, Goldman said, adding that “everybody knows what a loan is, right?”

Loans have so many advantages over advances that Credibly expects its loan business to grow more quickly than its advance business, said Goldman, who was formerly CEO of CAN Capital.

Those advantages are also encouraging other advance companies to form partnerships with banks to provide merchants with loans that aren’t subject to state commercial usury laws, said Robert Cook, a partner at Hudson Cook LLC, a Hanover, Md.-based financial services law firm.

The advance company markets the loan to the customer, the bank makes the loan, and the advance company buys it back and services it at the rate the bank is allowed under federal law, Cook said. The bank doesn’t lose any capital, it takes on virtually no risk and it profits by collecting a few days’ interest or a fee, he noted.

Where the bank’s located can make a big difference. A bank based in New York, for example, can charge only 25 percent interest no matter where the customer resides, while New Jersey allows banks to collect unlimited interest anywhere in the country, Cook said.

But the partnerships funders are forming with banks could face a threat. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in May in Madden v. Midland Funding LLC that a non-bank that buys a loan cannot charge interest set where the bank is located but must instead charge interest according to the laws of the state where the consumer is located, Cook noted. That could mean a lower rate.

In Cook’s view the case was poorly argued, the decision was wrong and the ruling may be reversed, “but it has to trouble someone who is thinking about starting up a bank partnership,” he said.

The court was asked whether the rules that apply to a national bank also apply to the non-bank that bought the loan, Cook maintained. That’s not the question, he asserted. The argument should have been that the idea of “valid when made” should take precedence. It states that a transaction that’s not usurious when it’s made doesn’t become usurious if a party takes action later – like reassigning the note, Cook said.

Meanwhile, offering bank loans isn’t the only way alternative funders are coming to resemble banks. Some are obtaining what’s formally called a California Finance Lenders License that enables them to make loans in that state.

California began requiring the license in response to lawsuits over the cost of advances. The state has published a licensee rulebook that’s about the size of an old-school New York phone book – the kind kids sat on to reach the dining room table, according to Yellowstone’s Stern, who completed the licensing process three years ago.

Getting the license took 15 or 16 months and required lots of help from the legal team at Hudson Cook, Stern said. The state investigated his back- ground and fingerprinted him. The cost, including lawyers’ fees came to about $60,000, he recalled.

“Man, it was like pulling teeth to get that license,” Stern said. Keeping it’s not easy, either. “We guard that thing fiercely,” he maintained. “They’ll take away your license if you even sneeze the wrong way.”

The hassles have paid off, though, because Yellowstone now deals directly with California customers instead of sharing the profits with other companies licensed to operate there. What’s more, companies that don’t have licenses are sending business Yellowstone’s way.

The hassles have paid off, though, because Yellowstone now deals directly with California customers instead of sharing the profits with other companies licensed to operate there. What’s more, companies that don’t have licenses are sending business Yellowstone’s way.

Retaining the profits from loans is also prompting some funders to contemplate applying for their own bank charters. But Cook, the attorney from Hudson Cook, sees little or no chance of that happening.

Federal bank regulators are reluctant to grant charters to mono-line banks – institutions that perform only one financial-services function, Cook said. “It’s risky to put all your eggs into one basket,” he maintained.

Regulations make forming or acquiring a bank so difficult for businesses that want to make small loans at high rates, Cook said. “If that’s going to be their business plan, they’re not going to get a bank.” A state charter requires the approval of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which isn’t likely, he noted.

Utah industrial banks and Utah industrial loan companies are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. but aren’t considered bank holding companies, Cook said. However, that’s a regulatory loophole that may have closed and thus may no longer offer a way of becoming a bank, he noted.

Clearly, the complications surrounding bank loans, lending licenses and bank charters mean that becoming more bank-like requires more than a pinstriped suit.