$100 Million in PPP Fees

May 12, 2020 $100 million. That’s the gross revenue floor that Ready Capital reported yesterday will be earned from its PPP loan origination efforts. PPP lenders earn between 1% to 5% of the loan amount in the form of a fee from the SBA and Ready Capital was the 15th largest PPP lender by dollars in the first round alone.

$100 million. That’s the gross revenue floor that Ready Capital reported yesterday will be earned from its PPP loan origination efforts. PPP lenders earn between 1% to 5% of the loan amount in the form of a fee from the SBA and Ready Capital was the 15th largest PPP lender by dollars in the first round alone.

The SBA pays 5% for loans under $350,000, 3% for loans between $350,000 and $2 million, and only 1% on loans over $2 million. With the majority of Ready Capital’s loans being for less than $350,000, the pure volume of loans originated (40,000+), translates into significantly larger fee income against a lender who may have originated the same dollar amount but with a much larger average loan size. JPMorgan’s average PPP loan size in Round 1, for example, was $515,000 (an average of a 3% fee) versus Ready Capital’s $73,000 (an average of a 5% fee).

Ready Capital clarified that on a net basis of those fees, they will take home substantially less, since the economics of those fees were in many cases split with referral agents and other partners that contributed in the process. Without committing to a firm figure, they estimated that their net revenue on PPP originations is actually going to be in the neighborhood of 35%-50% of the gross ($35 million to $50 million).

That is so far. Ready approved $3 billion in loans and has so far only funded $2.1 billion of them. The company said it expects that a large percentage that remain will still be funded and they will earn additional fee income respectively from those.

The company also addressed funding delays that had been reported across social media. “While there have been some challenges outside our control that have caused some delays in the distribution of funds, we have facilitated the funding of 2.1 billion through last Friday and are actively working through the remaining population to disperse funds as quickly as possible.”

Ready’s exposure on the loans themselves may be limited. The company said “we do not expect to carry much of the production on the balance sheet at all. So a very small portion will remain on the balance sheet. The majority of it will now be sold off balance sheet.”

The Three-Phase Guidelines for Reopening States

April 22, 2020 The Trump administration last week released a set of guidelines on how states and local governments may reopen.

The Trump administration last week released a set of guidelines on how states and local governments may reopen.

Titled ‘Opening Up America Again,’ the document outlines criteria to help classify which stage a region or state is in. Being a guideline rather than an order, it is not an exact prediction of how local and state economies will restart; with this process left to be decided by state governors rather than the president. As such, the plan omits details and specific requirements that would otherwise be left to the states.

The document notes a set of standards that must be met in order to prove eligible for entering each stage. Among these are practices being employed currently, like the establishment of contact tracing systems, increased ICU capacities, and the provision of testing sites for those who are symptomatic of covid-19. However, one standard, the adequate supplying of personal protection equipment and critical medical equipment, has proved difficult across the United States as ventilators, masks, and gowns worn by medical professionals are scarce.

If a state or region meets each of the listed criteria then it enters phase one. In this stage, services, individuals, and employers are suggested to act in their most limited capacity. Vulnerable individuals are asked to continue to shelter in place, and those who live with vulnerable individuals are asked to be mindful of going to work; gatherings of more than 10 people where strict physical distancing is not possible are to be avoided; non-essential travel is to be limited; telework is encouraged; staff common areas are to close; schools and organized youth activities are to be cancelled; large venues can open under strict physical distancing protocols, just as gyms can; and bars are to remain closed.

If the gating criteria are met a second time, the beginning of phase two is signaled. Here many of the guidelines stay the same, except the physical distancing standards are relaxed for large venues, schools may reopen, gatherings of up to 50 people are deemed safe so long as physical distancing is observed, non-essential travel can resume, and bars “may operate with diminished standing-room occupancy.”

And finally, if a state or region shows signs of no rebound of covid-19 and satisfy the gating criteria a third time, they enter the final phase. Vulnerable individuals may resume public interactions while practicing physical distancing; employers can reopen common areas; visits to senior living facilities and hospitals can resume; and large venues, bars, and gyms may operate under less restrictive protocols.

Again, the implementation of these guidelines remains an uncertainty. With states and governors being split over their reaction to the novel coronavirus as well as the level to which they are affected by the pandemic, it is unclear how

many, if any, will adhere to ‘Opening Up America Again.’

Maryland Legislative Committee to Meet On Merchant Cash Advance Prohibition (Rescheduled to Wednesday)

March 2, 2020Legislators in the Maryland State House will meet today on Wednesday at 1pm EST to discuss HB-1478, a bill to make merchant cash advances illegal in the state. A similar meeting is taking place tomorrow in the State Senate. The House meeting was originally scheduled for Monday but was postponed.

All four of the House bill’s sponsors are republicans. Today’s committee is expected to discuss the potential small business effect of prohibition. A legislative note that circulated before hand cautions that:

Any small businesses that utilize merchant cash advances, as defined by the bill, may be impacted, as the bill no longer allows such transactions. The Office of Commissioner of Financial Regulation advises that small businesses are likely to engage in merchant cash advance transactions, as they accept credit card payments and those receivables are their greatest source of liquidity. As such, prohibiting the use of such transactions may remove a source of financing that has traditionally been available to small businesses in the State. Additionally, prohibiting the use of merchant cash advance transactions may also affect small business lenders in the State that engage in these types of activities.

The bill, as written, would outlaw credit and debit card split transactions if it passed.

This bill prohibits a buyer from arranging, facilitating, or consummating a “merchant cash

advance transaction” with a seller in the State. The bill defines “merchant cash advance

transaction” as an arrangement between a buyer and a seller in which the buyer agrees to

purchase an agreed-on percentage of future credit or debit card revenues that are due to a

seller for a predetermined purchase price.

Canadian Lender’s Association Awards Leading Executives and Companies

November 11, 2019 Today the CLA announced the winners for its 2019 Leaders in Lending Awards. Highlighting the efforts of exceptional players within the fintech and alternative finance fields, the awards seek to “celebrate the industry and celebrate all the cool fintech things happening in Canada,” according to the CLA’s Strategic Partnerships Director Tal Schwartz.

Today the CLA announced the winners for its 2019 Leaders in Lending Awards. Highlighting the efforts of exceptional players within the fintech and alternative finance fields, the awards seek to “celebrate the industry and celebrate all the cool fintech things happening in Canada,” according to the CLA’s Strategic Partnerships Director Tal Schwartz.

Now in its second year, the Leaders in Lending Awards are split into two categories, with one focusing on the efforts of companies in the industry and the other on individual executives. 2019 will be the first year that the latter of these categories is incorporated. The awards will be imparted to their new owners at the Canadian Lenders Summit later this month, where a special prize will also be given to one winner from each category.

Among the winners in the first category are Borrowell, IOU Financial, and Michele Romanow’s Clearbanc. While making an appearance in the second category are David Gens of Merchant Growth, Paul Pitcher from SharpShooter Funding, Smarter Loans’ Vlad Sherbatov, and Kevin Clark from Lendified.

The criteria for the awards were based upon three tenets, these being a commitment to the “use of advanced fintech solutions” to solve challenges in the lending process, the “implementation of new or innovating lending strategies or business models,” and evidence of successful outcomes following the implementation of new fintech or a new business model.

When asked about possible expansions to the awards in the future, Schwartz was receptive to the idea of covering more ground with the prizes, saying “I definitely think we’ll expand the categories.” Mentioning that there’s a host of niches that are worth highlighting, such as blockchain, psychographic credit scoring, and credit rebuilding, which deserve their day in the sun.

“We have a mandate as a trade group to celebrate the industry,” emphasized Schwartz. And that celebration will be taking place on November 20th at the Canadian Lenders Summit in Toronto.

Mecklenburg County Launches Small Business Loan Program

October 10, 2019 This week Mecklenburg County, North Carolina launched its Small Business Loan Program. Offering up to $75,000 dollars with fixed 2% interest rates, the county has appropriated $2.75 million to fund the program for its first year. Being managed by the Carolina Small Business Development Fund, the CSBDF will have the authority to sign off on which small businesses will receive loans.

This week Mecklenburg County, North Carolina launched its Small Business Loan Program. Offering up to $75,000 dollars with fixed 2% interest rates, the county has appropriated $2.75 million to fund the program for its first year. Being managed by the Carolina Small Business Development Fund, the CSBDF will have the authority to sign off on which small businesses will receive loans.

Split into two tiers, one for businesses operating for less than two years or who are without revenue and the other for companies operating for at least two years, both tiers offer a micro loan and a conventional business loan. The former of these being a loan of less than $50,000 and the latter being one of over $50,000. Included with these loans are entrepreneurship training and mentoring.

Among the stipulations and requirements for the loans are that applicants have an annual revenue under $1 million and that they should not have any open tax liens, unpaid judgments, or principal and business bankruptcy in the previous five years. This risk-adverseness may be the definitive difference between such publicly provided funds and their private counterparts.

Accumulatively, the CSBDF has invested $59.7 million into programs such as these so far, with 735 loans having been authorized thus far.

Puff, Puff, Pass the Bill: House Approves Cannabis Banking Bill, Forwards it to Senate

October 10, 2019 Last month the House of Representatives passed the SAFE Banking Act, which provides for the lifting of red tape preventing cannabis companies from accessing banks and lenders.

Last month the House of Representatives passed the SAFE Banking Act, which provides for the lifting of red tape preventing cannabis companies from accessing banks and lenders.

Currently, such businesses are unable to make use of these financial services as regulators have put an outright ban on such dealings given cannabis’s federal Schedule 1 drug classification.

Having been approved 321-103, the House vote appeared bipartisan with almost half of the voting Republicans being in favor of SAFE. However, this is just the first step for the bill, as now it will be passed onto the Republican-held Senate, and then if it is approved there, the president’s office. With Republicans having demonstrated split attitudes towards legalization it is unclear which way the vote will go.

Regardless, the victory in the House has been celebrated by cannabis advocates and lobbyists alike. Talking to NBC, Platinum Vape President George Sadler described the vote as “a blessing.” While Aaron Smith, the Executive Director of the National Cannabis Industry Association, said that “it’s incredibly gratifying to see this strong bipartisan showing of support in today’s House vote … We owe a great debt of gratitude to the bill sponsors, who have been working with us to move this issue forward long before anyone else thought it was worth the effort … This bipartisan legislation is vital to protecting public safety, fostering transparency, and leveling the playing field for small businesses in the growing number of states with successful cannabis programs.”

For now though, no date has been set for the Senate vote on SAFE. With this version having been introduced by Senators Cory Gardner (R-CO) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR), and the Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo having recently asserted that cannabis banking legislation is being considered by his chamber, it appears as if this second round of voting may also benefit from bipartisan support.

Spotlight on AltFinanceDaily CONNECT Toronto

July 30, 2019 As the heat of the Toronto sun split the stones outside, the crowd inside the Omni King Edward’s seventeenth-floor Crystal Ballroom mingled and munched as part of AltFinanceDaily’s most recent CONNECT event.

As the heat of the Toronto sun split the stones outside, the crowd inside the Omni King Edward’s seventeenth-floor Crystal Ballroom mingled and munched as part of AltFinanceDaily’s most recent CONNECT event.

The first of its kind to be held in Toronto, the CONNECT series are half-day events that take place in both San Diego and Miami as well. Despite not being as established as the latter two, Toronto proved just as eventful, with a variety of speakers and topics broached, as well as a host of attendees from differing backgrounds making an appearance. It was par for the course for an inaugural AltFinanceDaily show with the attendance figures being reminiscent of AltFinanceDaily’s first ever event in the USA, a market that’s 10x the size.

The day was kicked off by entrepreneur, a dragon on the Canadian Dragons’ Den series, and co-founder of Clearbanc, Michele Romanow, whose anecdotes detailed the adventures that accompany the beginning of a startup. Regaling the audience with the story of Evandale Caviar, Romanow began with telling the room of a post-college venture that saw her working tooth and nail to secure a fishing license, studying YouTube fish gutting tutorials that were exclusively in Russian, and getting her hands dirty with the other co-founders when the time came to put their time spent online to use.

But it wasn’t all blood and glory for Romanow, as the tale shifted from one of youthful expansion to one of reflection and acceptance of the unknown. Speaking on the effect of tech giants in various fields, Romanow explained that “we have no idea of how these industries will shape out.” The likes of Uber and AirBnb never planned change the world, just to change a product and thus solve a problem, and their meteoric rises are unpredictable as a result. Iteration, rather than innovation, is what drives a company forward according to Romanow.

But it wasn’t all blood and glory for Romanow, as the tale shifted from one of youthful expansion to one of reflection and acceptance of the unknown. Speaking on the effect of tech giants in various fields, Romanow explained that “we have no idea of how these industries will shape out.” The likes of Uber and AirBnb never planned change the world, just to change a product and thus solve a problem, and their meteoric rises are unpredictable as a result. Iteration, rather than innovation, is what drives a company forward according to Romanow.

And this sentiment was brought further along with the following panel, which featured Vlad Sherbatov of Smarter Loans, Paul Pitcher of SharpShooter Funding, and SEO expert Paul Teitelman, speaking on the trials and novelties of the sales and marketing scene. Offering wisdom on various aspects of the field, the three men covered the need to go beyond the traditional forms of advertising, instead looking outward towards unorthodox methods of marketing; the hardships that come with the grind of a sales job; and the role that SEO can play when raising public awareness of your company; respectively.

“It’s a matter of spreading the word,” one conference goer noted when asked about the sales panel afterwards. “Businesses have to know who we are, and we’re working on that.”

“It’s a matter of spreading the word,” one conference goer noted when asked about the sales panel afterwards. “Businesses have to know who we are, and we’re working on that.”

Similarly, Martin Fingerhut and Adam Atlas discussed the existing legal topics of note to Canadian alternative financing companies, as well as those incoming rulings that may be worth knowing about. Covering both the English-speaking provinces and Quebec, the duo gave a comprehensive crash course on the legal landscape of the industry, highlighting laws unique to the regions. Aaron Iannello of Top Funding considered the talk to be particularly engaging, commending it for relaying information that might otherwise be unknown to American companies.

Following this, Kevin Clark, President of Lendified, took to the stage to talk about the importance of the Canadian Lenders Association (CLA). Saying that in the absence of a regulatory body, the CLA seeks to offer guidance to those companies who are looking for it. Clark asserted that “it’s a good thing for our industry to have oversight from a regularly body,” and that he looks forward to the day when one is established.

Following this, Kevin Clark, President of Lendified, took to the stage to talk about the importance of the Canadian Lenders Association (CLA). Saying that in the absence of a regulatory body, the CLA seeks to offer guidance to those companies who are looking for it. Clark asserted that “it’s a good thing for our industry to have oversight from a regularly body,” and that he looks forward to the day when one is established.

And before wrapping up the speakers for the day, Clark was joined by IOU Financial’s President, Robert Gloer, to discuss contemporary risk management. Covering everything from the next recession to the emergence of AI, the pair, which accumulatively have been in the industry for decades, offered knowledge learnt from years of experience in both the pre- and post-crash eras.

And the prophesizing of what will be the next big episode to shake the industry continued beyond the day’s scheduled agenda as many attendees continued on well into the evening at smaller networking functions offsite.

As the sun started to touchdown on the tips of Toronto’s skyscrapers, the salvo of excited conversation briefly harmonized to produce a singular axiom, that there was an abundance of opportunity in Canada.

So God Made a Farmer, But Who’s Financing The Farms?

May 1, 2019 Most mornings, farmers and ranchers wake up worrying about uncooperative weather and volatile commodity prices. Just the same, they pull themselves out of bed to spend the morning tinkering with crotchety machinery or wrangling uncooperative livestock. When they break for lunch, the kitchen radio alerts them to trade wars with distant countries and the unintended results of federal regulation. As they make their way back outdoors for the afternoon’s work, they can’t help but notice another new house taking shape in the distance as suburban sprawl encroaches on the fields and pastures. By evening, their thoughts have turned to their need for short-term capital and how the local banker seems increasingly wary of providing funds.

Most mornings, farmers and ranchers wake up worrying about uncooperative weather and volatile commodity prices. Just the same, they pull themselves out of bed to spend the morning tinkering with crotchety machinery or wrangling uncooperative livestock. When they break for lunch, the kitchen radio alerts them to trade wars with distant countries and the unintended results of federal regulation. As they make their way back outdoors for the afternoon’s work, they can’t help but notice another new house taking shape in the distance as suburban sprawl encroaches on the fields and pastures. By evening, their thoughts have turned to their need for short-term capital and how the local banker seems increasingly wary of providing funds.

It’s that last challenge where the alternative small-business funding industry might be able to help, says Peter Martin, a principal at K-Coe Isom, an accounting and consulting firm focused on the ag industry. “If you as a farmer need operating funds and you can’t get them from a bank, you don’t have a lot of options,” he says. “Historically, nobody outside of banks has had much interest in lending operating money to a farmer.”

The result of that reluctance to provide funding? “I can’t tell you the number of calls I get to say, ‘Hey, I need $100,000 and I need it in a couple of days because of X, Y, Z that’s come up,’” says Martin. “We don’t have a place that we can send those people to. You could make a lot of quick turnaround loans in rural America.” What’s more, it’s a potential clientele that makes a lot of money and prides itself on paying back what they owe.

Martin’s not alone in that assessment. While farmers enjoy abundant long-term credit to buy big-ticket assets, such as land and heavy machinery, they’re struggling to find sources of short-term credit for operating expenses like labor, repairs, fuel, seed, feed, fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides, notes Mike Gunderson, Purdue University professor of agricultural economics.

But remember that nobody’s saying it would be easy for alt funders to break into the agricultural sector. City folks accustomed to the fast-paced rhythms of New York or San Diego would have to learn a whole new seasonal business cycle. Grain farmers, for example, plant corn and soybeans in April, harvest their crops September or October, and may not sell the grain until the following January, says Nick Stokes, managing director of Conterra Asset Management, an alternative-funding company that places and services rural real estate loans.

But remember that nobody’s saying it would be easy for alt funders to break into the agricultural sector. City folks accustomed to the fast-paced rhythms of New York or San Diego would have to learn a whole new seasonal business cycle. Grain farmers, for example, plant corn and soybeans in April, harvest their crops September or October, and may not sell the grain until the following January, says Nick Stokes, managing director of Conterra Asset Management, an alternative-funding company that places and services rural real estate loans.

That seasonality results in revenue droughts punctuated by floods of revenue – a circumstance far-removed from the more-consistent credit card receipt split that launched the alternative small-business funding industry. Alternative funders seeking customers with consistent monthly cash flow won’t find them in the agricultural sector, Stokes cautions.

And while the unfamiliarity of farm life might begin with wild swings in cash flow, it doesn’t end there. Operating in the agricultural sector would require urbanites to learn the somewhat alien culture of The Heartland – a way of life based on hard physical labor, the fickle whims of the weather, and friendly unhurried conversations, even with strangers.

Even so, the task of mastering the agricultural funding market isn’t hopeless, and help’s available. Experts in agricultural economics profess a willingness to help outsiders learn what they need to know to get involved. “Selfishly, the first place I’d love to have them reach out to is me,” Martin says of alternative funders. “I’ve been writing and thinking for years about the importance of getting some non-traditional lenders into agriculture.” He would have “no qualms” about featuring specific prospective funders in a column he writes for one of the nation’s largest farm publications.

It also requires meet-and-greets. During the winter, when farmers aren’t in the fields, funders could make connections at trade shows, Martin advises. “Word would get around rural America really quick,” he predicts. Networking with advisers such as crop insurance agents, agronomists and ag CPS’s – all of whom deal with farmers daily – would also help funders find their way in agriculture, he contends.

It also requires meet-and-greets. During the winter, when farmers aren’t in the fields, funders could make connections at trade shows, Martin advises. “Word would get around rural America really quick,” he predicts. Networking with advisers such as crop insurance agents, agronomists and ag CPS’s – all of whom deal with farmers daily – would also help funders find their way in agriculture, he contends.

Investors who are curious about extending credit in the agricultural sector could rely upon Conterra to help them locate customers and help them service the loans, says Stokes. He can even help acclimate them to the world of agriculture. “If they’re interested in investing in agricultural assets – whether that be equipment, real estate or providing operating capital – we would enjoy the opportunity to visit with them,” he says.

GETTING STARTED

Alt funders could begin their introduction to the agrarian lifestyle by taking to heart a quotation attributed to President John F. Kennedy: “The farmer is the only man in our economy who buys everything at retail, sells everything at wholesale and pays the freight both ways.”

“Agriculture is a very different animal,” Martin notes. He sometimes presents a slide show to compare the difference between a typical farm and a typical manufacturer of the same size. At the factory, revenue ratchets up a bit each year and margins remain about the same over time. On the farm, revenue and margins both fluctuate wildly in huge peaks and valleys from one year to the next.

The volatility makes it difficult to manage the risk of lending, Martin admits, while noting that agriculturally oriented banks still have higher returns than non-ag banks, according to FDIC records. “You have to go back to 2006 to find a time when ag banks didn’t outperform their peers on return on assets,” he says. “What this tells us is that, generally speaking, ag borrowers are better at repaying their loans,” he asserts. Charge-offs and delinquencies in ag portfolios are lower than in other industries, he says.

Many of the nation’s farms have remained in the same family for more than a century – a stretch of time that’s seldom seen in just about any other type of business. Besides making potential creditors comfortable that a particular operation will stay in business, the longevity of farms provides lots of documents to examine – not just tax records but also production history that’s tracked by government agencies. A particular farmer’s crop yields, for example, can be compared with county averages to calculate how good the borrower is at farming.

Debt to asset ratio on the nation’s farms stands at about 14 percent, which Martin views as “insanely low.” But that’s not the case on every farm. Highly leveraged farms have ratios of 60 percent or even 80 percent when farmers have grown their businesses quickly or encountered debt to buy land from their parents, he says. Commodity prices are low now, but farms with 14 percent debt to asset ratios still don’t have a problem, even in hard times. Farmers deeply in debt, however, have little ability to climb out of the hole. The latter are using operating capital to fund losses.

Farmers with debt to asset ratios of 10 percent have little trouble finding credit and aren’t going to pay anything other than bank rates, Martin says. The target audience for non-traditional funding are farmers who are having trouble but will be fine when commodity prices rebound. Another potential client for alternative finance would be farmers who are quickly increasing the size of their operations when opportunities arise to acquire land. Both groups need funders willing to contemplate the future instead of demanding a perfect track record, he maintains.

Farmers with debt to asset ratios of 10 percent have little trouble finding credit and aren’t going to pay anything other than bank rates, Martin says. The target audience for non-traditional funding are farmers who are having trouble but will be fine when commodity prices rebound. Another potential client for alternative finance would be farmers who are quickly increasing the size of their operations when opportunities arise to acquire land. Both groups need funders willing to contemplate the future instead of demanding a perfect track record, he maintains.

Farmers generally need loans for operating capital for about 18 months, according to Martin. “Let’s say I borrow that money, get my crop in the ground, harvest that and I may not sell my grain right after harvest,” he says. The whole cycle can easily take 18 months, he says. Shorter-term bridge lending opportunities also arise in situations like needing a little extra cash quickly at harvest time. Farmers usually have something to put up as collateral – like producing 50 titles to vehicles or offering up some real estate, he says.

An unsecured loan – even one with high double-digit interest – could succeed in agriculture because no one is offering that type of funding, Martin says. Small and medium-sized farms would probably benefit from funding of $100,000 or less, while larger farms might sign up for that amount but often require more, he notes.

LAY OF THE LAND

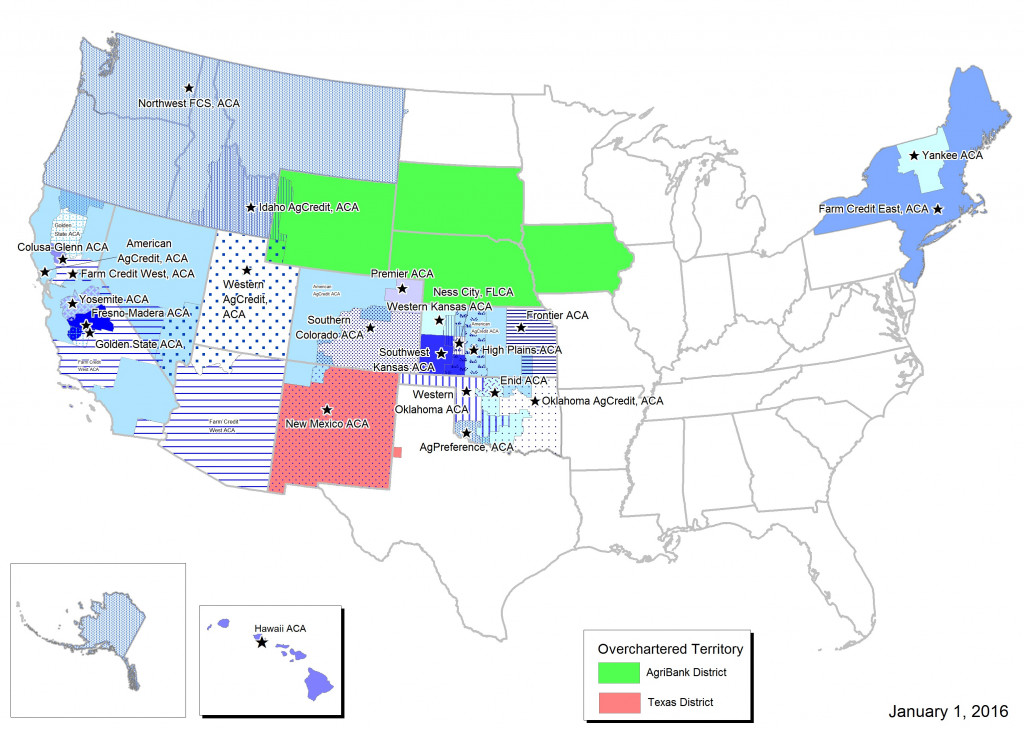

The Farm Credit System, a nationwide quasi-governmental network of borrower-owned lending institutions, provides more than a third of the credit granted in rural America. That comes to more than $304 billion annually in loans, leases and related services to farmers, ranchers, rural homeowners, aquatic producers, timber harvesters, agribusinesses, and agricultural and rural utility cooperatives, according to published reports.

Congress established the Farm Credit System in 1916, and the Farm Credit Administration was established in 1933 to provide regulatory oversight. “All they’re doing is lending money to agriculture,” says Martin.

However, the system can go astray in the eyes of some observers. An arm of the Farm Credit System called CoBank lends to co-operatives and other rural entities. At one point Verizon Wireless became a borrower from CoBank, which angered some observers because the system was supposed to be helping rural America, not corporate America, Martin says.

That anger arises partly because the federal government doesn’t require Farm Credit to pay income tax, which enables it to lend at lower rates, Martin says. “Part of the allure of borrowing from Farm Credit is you can typically borrow cheaper,” he notes. “You’d be very hard pressed to find a farmer who over the years hasn’t had some interaction with Farm Credit.”

Observers sometimes fault the system for what they perceive as a tendency to extend credit only to those who don’t really need it, notes Purdue’s Gunderson. People working for the system believe they’re doing a good job of supporting agriculture, he says, noting that the system is charged with the responsibility of helping new and young farmers.

Another entity, the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corp., also known as Famer Mac, works with lending institutions to provide credit to the agricultural sector. It’s a publicly traded company that serves as a secondary market in agricultural loans, including mortgages. It purchases loans and sells instruments backed by those loans and was chartered in 1988. Conterra, the alternative-funding company mentioned earlier in this article, -works with Farmer Mac and financial institutions to make real estate loans to farmers and ranchers in financial distress. The loans are designed to help borrowers get back on their feet in three to five years so that they would then qualify for regular bank loans.

Then there are the ag lending divisions at the large banks such as Wells Fargo, Chase and the Bank of the West, Martin says. “Lots of these big national banks are doing at least some ag lending,” he says. “Some, obviously, have bigger ag portfolios than others.”

Some regional banks focus on agriculture, Martin continues. “When you get into the middle of the corn belt, there are going to be some regional banks where traditional ag lending’s a huge part of what they do,” he says. Local banks in small towns get involved, too. “Most small community banks are going to have some kind of ag lending portfolio,” Martin notes. Hometown bankers can provide operating capital to some farmers, but only to those who haven’t experienced recent hiccups in revenue or expenses.

THE NON-BANKS

“Then you get into the non-bank lenders,” Martin observes. “A really good example of this is John Deere,” the tractor and equipment manufacturer. The company provides a tremendous amount of capital to rural America through equipment lending and also through other credit facilities, he says. In fact some observers estimate that John Deere is the largest lender to agriculture. Even so, the company usually doesn’t provide enough non-equipment credit to become the only lender a farmer would use, he says.

“Then you get into the non-bank lenders,” Martin observes. “A really good example of this is John Deere,” the tractor and equipment manufacturer. The company provides a tremendous amount of capital to rural America through equipment lending and also through other credit facilities, he says. In fact some observers estimate that John Deere is the largest lender to agriculture. Even so, the company usually doesn’t provide enough non-equipment credit to become the only lender a farmer would use, he says.

The same holds true with other lenders to agriculture, Martin says. Co-operatives, for example, lend money to agriculture even though they’re not banks. Typically, they begin by extending credit for products like seed, fertilizer or pesticides and then start making additional credit available to farms and ranches. In recent years, a large co-operative called CHS loaned hundreds of millions of dollars in addition to selling products on credit. Some large CHS loans went bad caused a ripple effect throughout the cooperative structure, Martin maintains. Other co-ops have looked at CHS and wondered if they’re moving too far outside their core competency. So now many co-ops are tying funding to products they’re selling.

Some other non-bank lenders have shown up in agriculture, and they fall into two categories, Martin says. One group is making real estate loans in agriculture, so their loan programs are geared to farmers looking to buy land or anything that can be secured by land. Conterra and Ag America are examples. Farmer Mac lends a lot of money against farmland, as well. So farmers who have agricultural land have a lot of access to capital and a lot of lenders who want to provide it, he says.

The second group of non-bank lenders is providing operating capital. “That is a very, very small club,” Martin says. “There’s really not anybody doing this on a regular basis – with just one or two exceptions.” Probably the biggest name among the exceptions is Ag Resource Management, usually known as ARM, he continues. ARM places a value on the potential productivity of a famer’s land. Then it looks at the crop insurance the farmer’s able to buy to protect the investment in that crop. ARM then lends part of the value of that crop insurance.

Let’s say a farmer can grow $10 million worth of crops, according to ARM’s projection,” Martin says. “You can get crop insurance to cover 80 percent,” he continues. “For a total crop failure, you will get $8 million for that crop.” Using a formula based on type of crop, location and type of crop insurance, ARM will lend some amount less than $8 million. “Their collateral is pretty rock solid,” Martin observes.

ARM uses a system to make sure farmers use the funds only for expenses related to growing the crop they’re using as collateral. “Their risk of not getting a crop in the ground that qualifies for the insurance is next to nothing,” Martin says. ARM offers differing interest rates, depending upon risk, in at least the high single digits or double digits, and they also charge fees. “So you’re going to be paying a lot, but they are the lender of last resort in agriculture right now,” he says, adding that ARM operates multiple offices has grown quickly.

Through lenders like ARM, the agricultural sector’s becoming familiar with alternative finance. But much remains to be done if alt fin pioneers want to venture into the sector. Those who do will encounter a complicated credit landscape, but one that offers opportunities for anyone willing to learn about unfamiliar business cycles and lifestyles.