Amazon Now Among The Top Online Small Business Lenders in The United States

May 8, 2019

Amazon has joined PayPal, OnDeck, Kabbage, and Square as being among the largest online small business lenders. On Tuesday, Amazon revealed that it had made more than $1 billion in small business loans to US-based merchants in 2018. Amazon says the capital is used to build inventory and support their Amazon stores.

By selling on Amazon, “SMBs do not need to invest in a physical store or the costs of customer discovery, acquisition, and driving customer traffic to their branded websites,” the company says. Small and medium-sized businesses selling in Amazon’s stores now account for 58 percent of Amazon’s sales. More than 200,000 SMBs exceeded $100,000 in sales on Amazon in 2018 and more than 25,000 surpassed $1 million.

You can view the full report they published here.

| Company Name | 2018 Originations | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| PayPal | $4,000,000,000* | $750,000,000* | ||||

| OnDeck | $2,484,000,000 | $2,114,663,000 | $2,400,000,000 | $1,900,000,000 | $1,200,000,000 | |

| Kabbage | $2,000,000,000 | $1,500,000,000 | $1,220,000,000 | $900,000,000 | $350,000,000 | |

| Square Capital | $1,600,000,000 | $1,177,000,000 | $798,000,000 | $400,000,000 | $100,000,000 | |

| Amazon | $1,000,000,000 | |||||

| Funding Circle (USA only) | $792,000,000 | $514,000,000 | $281,000,000 | |||

| BlueVine | $500,000,000* | $200,000,000* | ||||

| National Funding | $494,000,000 | $427,000,000 | $350,000,000 | $293,000,000 | ||

| Kapitus | $393,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $280,000,000 | ||

| BFS Capital | $300,000,000 | $300,000,000 | $300,000,000 | |||

| RapidFinance | $260,000,000 | $280,000,000 | $195,000,000 | |||

| Credibly | $290,000,000 | $180,000,000 | $150,000,000 | $95,000,000 | $55,000,000 | |

| Shopify | $277,100,000 | $140,000,000 | ||||

| Forward Financing | $210,000,000 | $125,000,000 | ||||

| IOU Financial | $125,000,000 | $91,300,000 | $107,600,000 | $146,400,000 | $100,000,000 | |

| Yalber | $65,000,000 |

Has PayPal Eclipsed OnDeck in Small Business Loans?

April 26, 2019

It’s been said that Kabbage is on pace to surpass OnDeck in small business loan originations, but PayPal has already done it.

When PayPal announced a working capital program in the Fall of 2013, few were predicting that the initiative would propel them to the top of the small business lending charts. Just two years later, however, the payment processing giant had already loaned more than $1 billion to small businesses.

Today, that number is over $10 billion, according to a comment made by PayPal CEO Dan Schulman on the company’s Q1 earnings call.

That figure would suggest that they had loaned approximately $9 billion from Fall 2015 to the end of Q1 2019. OnDeck, by comparison, loaned $7.5 billion since Fall 2015 through Q4 2018. Several other data sources, including previous statements from PayPal that they had surpassed more than a billion dollars in quarterly small business funding in 2018 (already more than OnDeck), indicate that PayPal has become #1 on the AltFinanceDaily small business funding leaderboard.

PayPal’s growth was helped in part by its acquisition of Swift Capital in 2017.

Two of the top four are payment processors:

| Company Name | 2018 Originations | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| PayPal | $4,000,000,000* | $750,000,000* | ||||

| OnDeck | $2,484,000,000 | $2,114,663,000 | $2,400,000,000 | $1,900,000,000 | $1,200,000,000 | |

| Kabbage | $2,000,000,000 | $1,500,000,000 | $1,220,000,000 | $900,000,000 | $350,000,000 | |

| Square Capital | $1,600,000,000 | $1,177,000,000 | $798,000,000 | $400,000,000 | $100,000,000 | |

| Funding Circle (USA only) | $500,000,000 | |||||

| BlueVine | $500,000,000* | $200,000,000* | ||||

| National Funding | $427,000,000 | $350,000,000 | $293,000,000 | |||

| Kapitus | $393,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $280,000,000 | ||

| BFS Capital | $300,000,000 | $300,000,000 | ||||

| RapidFinance | $260,000,000 | $280,000,000 | $195,000,000 | |||

| Credibly | $180,000,000 | $150,000,000 | $95,000,000 | $55,000,000 | ||

| Shopify | $277,100,000 | $140,000,000 | ||||

| Forward Financing | $125,000,000 | |||||

| IOU Financial | $91,300,000 | $107,600,000 | $146,400,000 | $100,000,000 | ||

| Yalber | $65,000,000 |

*Asterisks signify that the figure is the editor’s estimate

< 5% Annual Returns On Small Business Loans?

April 25, 2019 If you were to invest in small business loans with 4-year terms, what kind of return would you hope to get?

If you were to invest in small business loans with 4-year terms, what kind of return would you hope to get?

Retail investors that put their money in a mix of high-risk and low-risk loans on Funding Circle’s UK platform should expect to achieve a return of 4.5% to 6.5% a year (after defaults and 1% servicing fee), the company recently announced. That’s down from their previous projections. Meanwhile, their conservative loans could achieve returns of 4.3% to 4.7% a year.

A Marcus By Goldman Sachs savings account in the UK by comparison earns 1.50%

Funding Circle explained in a blog post that the returns could actually be higher or lower than projected.

To-date, investor interest has continued to grow with peers on the platform investing £1.5 billion in 2018 and £419 million in the 1st quarter of 2019.

Lending Club Calls It Quits On Underwriting Small Business Loans

April 23, 2019

Lending Club will no longer be underwriting small business loans, according to Lending Club Head of Communication VP Anuj Nayar. The company will still accept applications for them, but will direct them instead to Opportunity Fund and Funding Circle in exchange for referral fees. Less established businesses, or those with lesser credit, will be sent to Opportunity Fund, while more established businesses with better credit will go to Funding Circle.

According to Nayar, there will be no layoffs. Some employees who had worked in small business underwriting will move elsewhere within Lending Club while others will become contractors for Opportunity Fund. Opportunity Fund is a non-profit with the mission of investing in small businesses that have been shut out of the financial mainstream. It is backed by major financial institutions including Bank of America, Goldman Sachs and the JP Morgan Chase and Knight Foundations. In fiscal year 2017, Opportunity Fund made over $92.5 million in loans to more than 2,900 small business owners.

“[These two partnerships] enables us to both deliver greater value to our applicants and capture a new revenue stream for Lending Club, while further simplifying our business and setting the stage for more partnerships and innovations for Club Members,” said Lending Club CEO Scott Sanborn.

The new revenue stream Sanborn refers to is the referral fees Lending Club will get from its new funding partners when they fund loans sent to them from Lending Club. And Lending Club’s business will be streamlined as it jettisons small business lending backend operations. They will now focus exclusively on consumer loans, which has been the company’s primary business since it was founded in 2006.

Lending Club expanded into small business lending several years ago, but this component of its business never really took off, and was declining over the last few years. At the end of December 2016, Lending Club’s non-consumer loan originations (including small business loans) accounted for 10% of its business. In December 2017, it was 9%. And in the fourth quarter of 2018, it was 7%.

Nayar said that these new partnerships will allow Lending Club to focus even more on consumer lending. Headquartered in San Francisco, Lending Club has lent more than $44 billion to 2.5 million customers.

Competition Steps Up in Canadian Small Business Lending Market

March 11, 2019 Last week’s announcement by Funding Circle that it will establish an operation in Canada later this year is part of a trend of large non-Canadian funders entering or expanding into the Canadian market, according to Adam Benaroch, President of CanaCap, a small business funder based in Montreal.

Last week’s announcement by Funding Circle that it will establish an operation in Canada later this year is part of a trend of large non-Canadian funders entering or expanding into the Canadian market, according to Adam Benaroch, President of CanaCap, a small business funder based in Montreal.

Funding Circle started in the UK and expanded outwards to the US, Germany, and The Netherlands, but the UK still comprises of more than 60% of their global origination volume. Their foray into Canada is a good thing for small business owners and lenders, according to Paul Pitcher, founder and CEO of SharpShooter, a funder based in Toronto.

“I see it as win-win,” Pitcher said.

He said that a win for Canadian small business owners is a win for SharpShooter because it means more potential merchant clients. Pitcher said that he loves OnDeck, a rival, is in Canada, in part because OnDeck’s marketing has helped educate Canadian merchants about alternative lending products.

Similarly, Benaroch said he thinks that big companies entering the Canadian market will affect CanaCap positively. For instance, Benaroch said that CanaCap hopes to capture companies that get turned down from OnDeck. And perhaps CanaCap can also capture merchants that are declined by Funding Circle.

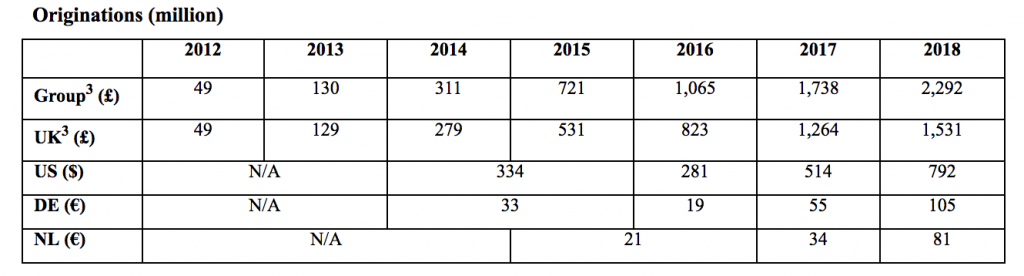

Funding Circle’s loan originations by country by year

Funding Circle’s loan originations by country by year

Benaroch noted that not all outside funding companies have succeeded in Canada, often because they never established a physical presence there. But Funding Circle will be opening a physical office in Toronto.

“We have been evaluating options for expansion over the last year,” said Tom Eilon, who will be Managing Director of Funding Circle Canada. “Canada’s stable, growing economy coupled with good access to credit data and a progressive regulatory environment, made it the obvious choice. The most important factor [in coming to Canada] though was the clear need for additional funding options among Canadian SMEs.”

Funding Circle’s announcement comes on the heels of OnDeck’s December 2018 acquisition of Evolocity Financial Group, a small business funder based in Montreal. While OnDeck started operating in Canada as early as 2015, CanaCap’s Adam Benaroch said that the acquisition of Evolocity is a significant step for OnDeck because Evolocity has an ISO channel in Canada. That runs counter to Funding Circle’s model of mainly going direct to merchant, at least in the US.

Shopify is Quickly Climbing the Ranks of the Largest Small Business Funders

February 12, 2019Shopify originated $277 million in merchant cash advances in 2018, according to their quarterly earnings reports. That figure already places them among the largest small business funding providers nationwide.

Below is a look of how they stack up thus far:

| Company Name | 2018 Originations | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

| OnDeck | $2,484,000,000 | $2,114,663,000 | $2,400,000,000 | $1,900,000,000 | $1,200,000,000 | |

| Kabbage | $2,000,000,000 | $1,500,000,000 | $1,220,000,000 | $900,000,000 | $350,000,000 | |

| Square Capital | $1,600,000,000 | $1,177,000,000 | $798,000,000 | $400,000,000 | $100,000,000 | |

| Funding Circle (USA only) | $500,000,000 | |||||

| BlueVine | $500,000,000* | $200,000,000* | ||||

| National Funding | $427,000,000 | $350,000,000 | $293,000,000 | |||

| Kapitus | $393,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $375,000,000 | $280,000,000 | ||

| BFS Capital | $300,000,000 | $300,000,000 | ||||

| RapidFinance | $260,000,000 | $280,000,000 | $195,000,000 | |||

| Credibly | $180,000,000 | $150,000,000 | $95,000,000 | $55,000,000 | ||

| Shopify | $277,100,000 | $140,000,000 | ||||

| Forward Financing | $125,000,000 | |||||

| IOU Financial | $91,300,000 | $107,600,000 | $146,400,000 | $100,000,000 | ||

| Yalber | $65,000,000 |

*Asterisks signify that the figure is the editor’s estimate

Less Than Perfect — New State Regulations

December 21, 2018

You could call California’s new disclosure law the “Son-in-Law Act.” It’s not what you’d hoped for—but it’ll have to do.

That’s pretty much the reaction of many in the alternative lending community to the recently enacted legislation, known as SB-1235, which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in October. Aimed squarely at nonbank, commercial-finance companies, the law—which passed the California Legislature, 28-6 in the Senate and 72-3 in the Assembly, with bipartisan support—made the Golden State the first in the nation to adopt a consumer style, truth-in-lending act for commercial loans.

The law, which takes effect on Jan. 1, 2019, requires the providers of financial products to disclose fully the terms of small-business loans as well as other types of funding products, including equipment leasing, factoring, and merchant cash advances, or MCAs.

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

The financial disclosure law exempts depository institutions—such as banks and credit unions—as well as loans above $500,000. It also names the Department of Business Oversight (DBO) as the rulemaking and enforcement authority. Before a commercial financing can be concluded, the new law requires the following disclosures:

(1) An amount financed.

(2) The total dollar cost.

(3) The term or estimated term.

(4) The method, frequency, and amount of payments.

(5) A description of prepayment policies.

(6) The total cost of the financing expressed as an annualized rate.

The law is being hailed as a breakthrough by a broad range of interested parties in California—including nonprofits, consumer groups, and small-business organizations such as the National Federation of Independent Business. “SB-1235 takes our membership in the direction towards fairness, transparency, and predictability when making financial decisions,” says John Kabateck, state director for NFIB, which represents some 20,000 privately held California businesses.

“What our members want,” Kabateck adds, “is to create jobs, support their communities, and pursue entrepreneurial dreams without getting mired in a loan or financial structure they know nothing about.”

Backers of the law, reports Bloomberg Law, also included such financial technology companies as consumer lenders Funding Circle, LendingClub, Prosper, and SoFi.

But a significant segment of the nonbank commercial lending community has reservations about the California law, particularly the requirement that financings be expressed by an annualized interest rate (which is different from an annual percentage rate, or APR). “Taking consumer disclosure and annualized metrics and plopping them on top of commercial lending products is bad public policy,” argues P.J. Hoffman, director of regulatory affairs at the Electronic Transactions Association.

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

The ETA is a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing nearly 500 payments technology companies worldwide, including such recognizable names as American Express, Visa and MasterCard, PayPal and Capital One. “If you took out the annualized rate,” says ETA’s Hoffman, “we think the bill could have been a real victory for transparency.”

California’s legislation is taking place against a backdrop of a balkanized and fragmented regulatory system governing alternative commercial lenders and the fintech industry. This was recognized recently by the U.S. Treasury Department in a recently issued report entitled, “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation.” In a key recommendation, the Treasury report called on the states to harmonize their regulatory systems.

As laudable as California’s effort to ensure greater transparency in commercial lending might be, it’s adding to the patchwork quilt of regulation at the state level, says Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute. “Now it’s every regulator for himself or herself,” he says.

Hurley is collaborating with Jason Oxman, executive director of ETA, Oklahoma University law professor Christopher Odinet, and others from the online-lending industry, the legal profession, and academia to form a task force to monitor the progress of regulatory harmonization.

For now, though, all eyes are on California to see what finally emerges as that state’s new disclosure law undergoes a rulemaking process at the DBO. Hoffman and others from industry contend that short-term, commercial financings are a completely different animal from consumer loans and are hoping the DBO won’t squeeze both into the same box.

Steve Denis, executive director of the Small Business Finance Association, which represents such alternative financial firms as Rapid Advance, Strategic Funding and Fora Financial, is not a big fan of SB-1235 but gives kudos to California solons—especially state Sen. Steve Glazer, a Democrat representing the Bay Area who sponsored the disclosure bill—for listening to all sides in the controversy. “Now, the DBO will have a comment period and our industry will be able to weigh in,” he notes.

While an annualized rate is a good measuring tool for longer-term, fixed-rate borrowings such as mortgages, credit cards and auto loans, many in the small-business financing community say, it’s not a great fit for commercial products. Rather than being used for purchasing consumer goods, travel and entertainment, the major function of business loans are to generate revenue.

A September, 2017, study of 750 small-business owners by Edelman Intelligence, which was commissioned by several trade groups including ETA and SBFA, found that the top three reasons businesses sought out loans were “location expansion” (50%), “managing cash flow” (45%) and “equipment purchases” (43%).

The proper metric to be employed for such expenditures, Hoffman says, should be the “total cost of capital.” In a broadsheet, Hoffman’s trade group makes this comparison between the total cost of capital of two loans, both for $10,000.

Loan A for $10,000 is modeled on a typical consumer borrowing. It’s a five-year note carrying an annual percentage rate of 19%—about the same interest rate as many credit cards—with a fixed monthly payment of $259.41. At the end of five years, the debtor will have repaid the $10,000 loan plus $5,564 in borrowing costs. The latter figure is the total cost of capital.

Compare that with Loan B. Also for $10,000, it’s a six month loan paid down in monthly payments of $1,915.67. The APR is 59%, slightly more than three times the APR of Loan A. Yet the total cost of capital is $1,500, a total cost of capital which is $4,064.33 less than that of Loan A.

Meanwhile, Hoffman notes, the business opting for Loan B is putting the money to work. He proposes the example of an Irish pub in San Francisco where the owner is expecting outsized demand over the upcoming St. Patrick’s Day. In the run-up to the bibulous, March 17 holiday, the pub’s owner contracts for a $10,000 merchant cash advance, agreeing to a $1,000 fee.

Once secured, the money is spent stocking up on Guinness, Harp and Jameson’s Irish whiskey, among other potent potables. To handle the anticipated crush, the proprietor might also hire temporary bartenders.

When St. Patrick’s Day finally rolls around—thanks to the bulked-up inventory and extra help—the barkeep rakes in $100,000 and, soon afterwards, forwards the funding provider a grand total of $11,000 in receivables. The example of the pub-owner’s ability to parlay a short-term financing into a big payday illustrates that “commercial products—where the borrower is looking for a return on investment—are significantly different from consumer loans,” Hoffman says.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

SBFA’s Denis observes that financial products like merchant cash advances are structured so that the provider of capital receives a percentage of the business’s daily or weekly receivables. Not only does that not lend itself easily to an annualized rate but, if the food truck, beautician, or apothecary has a bad day at the office, so does the funding provider. “It’s almost like the funding provider is taking a ride” with the customer, says Denis.

Consider a cash advance made to a restaurant, for instance, that needs to remodel in order to retain customers. “An MCA is the purchase of future receivables,” Denis remarks, “and if the restaurant goes out of business— and there are no receivables—you’re out of luck.”

Still, the alternative commercial-lending industry is not speaking with one voice. The Innovative Lending Platform Association—which counts commercial lenders OnDeck, Kabbage and Lendio, among other leading fintech lenders, as members—initially opposed the bill, but then turned “neutral,” reports Scott Stewart, chief executive of ILPA. “We felt there were some problems with the language but are in favor of disclosure,” Stewart says.

The organization would like to see DBO’s final rules resemble the company’s model disclosure initiative, a “capital comparison tool” known as “SMART Box.” SMART is an acronym for Straightforward Metrics Around Rate and Total Cost—which is explained in detail on the organization’s website, onlinelending.org.

But Kabbage, a member of ILPA, appears to have gone its own way. Sam Taussig, head of global policy at Atlanta-based financial technology company Kabbage told AltFinanceDaily that the company “is happy with the result (of the California law) and is working with DBO on defining the specific terms.”

Others like National Funding, a San Diego-based alternative lender and the sixth-largest alternative-funding provider to small businesses in the U.S., sat out the legislative battle in Sacramento. David Gilbert, founder and president of the company, which boasted $94.5 million in revenues in 2017, says he had no real objection to the legislation. Like everyone else, he is waiting to see what DBO’s rules look like.

“It’s always good to give more rather than less information,” he told AltFinanceDaily in a telephone interview. “We still don’t know all the details or the format that (DBO officials) want. All we can do is wait. But it doesn’t change this business. After the car business was required to disclose the full cost of motor vehicles,” Gilbert adds, “people still bought cars. There’s nothing here that will hinder us.”

With its panoply of disclosure requirements on business lenders and other providers of financial services, California has broken new legal ground, notes Odinet, the OU law professor, who’s an expert on alternative lending and financial technology. “Not many states or the federal government have gotten involved in the area of small business credit,” he says. “In the past, truth-in-lending laws addressing predatory activities were aimed primarily at consumers.”

The financial-disclosure legislation grew out of a confluence of events: Allegations in the press and from consumer activists of predatory lending, increasing contraction both in the ranks of independent and community banks as well as their growing reluctance to make small-business loans of less than $250,000, and the rise of alternative lenders doing business on the Internet.

In addition, there emerged a consensus that many small businesses have more in common with consumers than with Corporate America. Rather than being managed by savvy and sophisticated entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley with a Stanford pedigree, many small businesses consist of “a man or a woman working out of their van, at a Starbucks, or behind a little desk in their kitchen,” law professor Odinet says. “They may know their business really well, but they’re not really in a position to understand complicated financial terms.”

The average small-business owner belonging to NFIB in California, reports Kabateck, has $350,000 in annual sales and manages from five to nine employees. For this cohort—many of whom are subject to myriad marketing efforts by Internet-based lenders offering products with wildly different terms—the added transparency should prove beneficial. “Unlike big businesses, many of them don’t have the resources to fully understand their financial standing,” Kabateck says. “The last thing they want is to get steeped in more red ink or—even worse—have the wool pulled over their eyes.”

California’s disclosure law is also shaping up as a harbinger—and perhaps even a template—for more states to adopt truth-in-lending laws for small-business borrowers. “California is the 800-lb. gorilla and it could be a model for the rest of the country,” says law professor Hurley. “Just as it has taken the lead on the control of auto emissions and combating climate change, California is taking the lead for the better on financial regulation. Other states may or may not follow.”

California’s disclosure law is also shaping up as a harbinger—and perhaps even a template—for more states to adopt truth-in-lending laws for small-business borrowers. “California is the 800-lb. gorilla and it could be a model for the rest of the country,” says law professor Hurley. “Just as it has taken the lead on the control of auto emissions and combating climate change, California is taking the lead for the better on financial regulation. Other states may or may not follow.”

Reflecting the Golden State’s influence, a truth-in-lending bill with similarities to California’s, known as SB-2262, recently cleared the state senate in the New Jersey Legislature and is on its way to the lower chamber. SBFA’s Denis says that the states of New York and Illinois are also considering versions of a commercial truth-in-lending act.

But the fact that these disclosure laws are emanating out of Democratic states like California, New Jersey, Illinois and New York has more to do with their size and the structure of the states’ Legislatures than whether they are politically liberal or conservative. “The bigger states have fulltime legislators,” Denis notes, “and they also have bigger staffs. That’s what makes them the breeding ground for these things.”

Buried in Appendix B of Treasury’s report on nonbank financials, fintechs and innovation is the recommendation that, to build a 21st century economy, the 50 states should harmonize and modernize their regulatory systems within three years. If the states fail to act, Treasury’s report calls on Congress to take action.

The triumvirate of Hurley, Oxman and Odinet report, meanwhile, that they are forming a task force and, with the tentative blessing of Treasury officials, are volunteering to monitor the states’ progress. “I think we have an opportunity as independent representatives to help state regulators and legislators understand what they can do to promote innovation in financial services,” ETA’s Oxman asserts.

The ETA is a lobbying organization, Oxman acknowledges, but he sees his role—and the task force’s role—as one of reporting and education. He expects to be meeting soon with representatives of the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), the Washington, D.C.-based organization representing regulators of state chartered banks. It is also the No. 1 regulator of nonbanks and fintechs. “They are the voice of state financial regulators,” Oxman says, “and they would be an important partner in anything we do.”

The ETA is a lobbying organization, Oxman acknowledges, but he sees his role—and the task force’s role—as one of reporting and education. He expects to be meeting soon with representatives of the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS), the Washington, D.C.-based organization representing regulators of state chartered banks. It is also the No. 1 regulator of nonbanks and fintechs. “They are the voice of state financial regulators,” Oxman says, “and they would be an important partner in anything we do.”

Margaret Liu, general counsel at CSBS, had high praise for Treasury’s hard work and seriousness of purpose in compiling its 200-plus page report and lauded the quality of its research and analysis. But Liu noted that the conference was already deeply engaged in a program of its own, which predates Treasury’s report.

Known as “Vision 2020,” the program’s goals, as articulated by Texas Banking Commissioner Charles Cooper, are for state banking regulators to “transform the licensing process, harmonize supervision, engage fintech companies, assist state banking departments, make it easier for banks to provide services to non-banks, and make supervision more efficient for third parties.”

While CSBS has signaled its willingness to cooperate with Treasury, the conference nonetheless remains hostile to the agency’s recommendation, also found in the fintech report, that the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issue a “special purpose national bank charter” for fintechs. So vehemently opposed are state bank regulators to the idea that in late October the conference joined the New York State Banking Department in re-filing a suit in federal court to enjoin the OCC, which is a division of Treasury, from issuing such a charter.

Among other things, CSBS’s lawsuit charges that “Congress has not granted the OCC authority to award bank charters to nonbanks.”

Previously, a similar lawsuit was tossed out of court because, a judge ruled, the case was not yet “ripe.” Since no special purpose charters had actually been issued, the judge ruled, the legal action was deemed premature. That the conference would again file suit when no fintech has yet applied for a special purpose national bank charter— much less had one approved—is baffling to many in the legal community.

“I suspect the lawsuit won’t go anywhere” because ripeness remains a sticking point, reckons law professor Odinet. “And there’s no charter pending,” he adds, in large part because of the lawsuit. “A lot of people are signing up to go second,” he adds, “but nobody wants to go first.”

Treasury’s recommendation that states harmonize their regulatory systems overseeing fintechs in three years or face Congressional action also seems less than jolting, says Ross K. Baker, a distinguished professor of political science at Rutgers University and an expert on Congress. He told AltFinanceDaily that the language in Treasury’s document sounded aspirational but lacked any real force.

“Usually,” he says, such as a statement “would be accompanied by incentives to do something. This is a kind of a hopeful urging. But I don’t see any club behind the back,” he went on. “It seems to be a gentle nudging, which of course they (the states) are perfectly able to ignore. It’s desirable and probably good public policy that states should have a nationwide system, but it doesn’t say Congress should provide funds for states to harmonize their laws.

“When the Feds issue a mandate to the states,” Baker added, “they usually accompany it with some kind of sweetener or sanction. For example, in the first energy crisis back in 1973, Congress tied highway funds to the requirement (for states) to lower the speed limit to 55 miles per hour. But in this case, they don’t do either.”

The Seven-Minute Loan Shakes Up Washington And The 50 States

August 19, 2018 It takes seven minutes for Kabbage to approve a small-business loan. “The reason there’s so little lag time,” says Sam Taussig, head of global policy at the Atlanta-based financial technology firm, “is that it’s all automated. Our marginal cost for loans is very low,” he explains, “because everything involving the intake of information – your name and address, know-your-customer, anti-money-laundering and anti-terrorism checks, analyzing three years of income statements, cash-flow analysis – is one-hundred-percent automated. There are no people involved unless red flags go off.”

It takes seven minutes for Kabbage to approve a small-business loan. “The reason there’s so little lag time,” says Sam Taussig, head of global policy at the Atlanta-based financial technology firm, “is that it’s all automated. Our marginal cost for loans is very low,” he explains, “because everything involving the intake of information – your name and address, know-your-customer, anti-money-laundering and anti-terrorism checks, analyzing three years of income statements, cash-flow analysis – is one-hundred-percent automated. There are no people involved unless red flags go off.”

One salient testament to Kabbage’s automation: Fully $1 billion of the $5 billion in loans that it has made to 145,000 discrete borrowers since it opened its portals in 2011 were made between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m.

Now compare that hair-trigger response time and 24-hour service for a small business loan of $1,000-$250,000 with what occurs at a typical bank. “Corporate credit underwriting requires 28 separate tasks to arrive at a decision,” William Phelan, president, and co‐founder of PayNet—a top provider of small-business credit data and analysis – testified recently to a Congressional subcommittee. “These 28 tasks involve (among other things): collecting information for the credit application, reviewing the financial information, data entry and calculations, industry analysis, evaluation of borrower capability, capacity (to repay), and valuation of collateral.”

A “time-series analysis,” the Skokie (Ill.)-based executive went on, found that it takes two-to-three weeks – and often as many as eight weeks—to complete the loan approval process. For this “single credit decision,” Phelan added, the services of three bank departments – relationship manager, credit analyst, and credit committee – are required.

The cost of such a labor-intensive operation? PayNet analysts reckoned that banks incur $4,000-$6,000 in underwriting expenses for each credit application. Phelan said, moreover, that credit underwriting typically includes a subsequent loan review, which consumes two days of effort and costs the bank an additional $1,000. “With these costs,” Phelan told lawmakers, “banks are unable to turn a profit unless the loan size exceeds $500,000.”

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the country’s very biggest banks — Bank of America, Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo—have been the financial institutions most likely to shut down lending to small businesses. “While small business lending declined at all banks beginning in 2008,” NBER’s September, 2017 report announces, “the four largest banks” which the report dubs the ‘Top Four’—“cut back significantly relative to the rest of the banking sector.”

NBER reports further that by 2010—the “trough” of the financial crisis—the annual flow of loan originations from the Top Four stood at just 41% of its 2006 level, which compared with 66% of the pre-crisis level for all other banks. Moreover, small-business lending at the “Top Four” banks remained suppressed for several years afterward, “hovering” at roughly 50% of its pre crisis level through 2014. By contrast, such lending at the rest of the country’s banks eventually bounced back to nearly 80% of the pre-crisis level by 2014.

That pullback—by all banks—continues, says Kenneth Singleton, an economics professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. Echoing Phelan’s testimony, Singleton told AltFinanceDaily in an interview: “Given the high underwriting costs, banks just chose not to make loans under $250,000,” which are the bread-and-butter of small-business loans. In so doing, he adds, banks “have created a vacuum for fintechs.”

All of which helps explain why Kabbage and other fintechs making small business loans are maintaining a strong growth trajectory. As a Federal Reserve report issued in June notes, the five most prominent fintech lenders to small businesses—OnDeck, Kabbage, Credibly, Square Capital, and PayPal—are on track to grow by an estimated 21.5 percent annually through 2021.

Their outsized growth is just one piece—albeit a major one—of fintech’s larger tapestry. Depending on how you define “financial technology,” there are anywhere from 1,400 to 2,000 fintechs operating in the U.S., experts say. Fintech companies are now engaged in online payments, consumer lending, savings and investment vehicles, insurance, and myriad other forms of financial services.

Fintechs’ advocates—a loose confederacy that includes not only industry practitioners but also investors, analysts, academics, and sympathetic government officials—assert that the U.S. fintech industry is nonetheless being blunted from realizing its full potential. If fintechs were allowed to “do their thing,” (as they said in the sixties) this cohort argues, a supercharged industry would bring “financial inclusion” to “unbanked” and “underbanked” populations in the U.S. By “democratizing access to capital,” as Kabbage’s Taussig puts it, harnessing technology would also re-energize the country’s small businesses, which creates the majority of net new jobs in the U.S., according to the U.S. Small Business Administration.

But standing in the way of both innovation and more robust economic growth, this cohort asserts, is a breathtakingly complex—and restrictive—regulatory system that dates back to the Civil War. “I do think we’re victims of our own success in that we’ve got a pretty good financial system and a pretty good regulatory structure where most people can make payments and the vast majority of people can get credit.” says Jo Ann Barefoot, chief executive at Barefoot Innovation Group in Washington, D.C. and a former senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School. But because of that “there’s been more inertia and slower adoption of new technology,” she adds. “People in the U.S. are still going to bank branches more than people in the rest of the world.”

Barefoot adds: “There are five agencies directly overseeing financial services at the Federal level and another two dozen federal agencies” providing some measure of additional, if not duplicative oversight, over financial services. “But there’s no fintech licensing at the national level,” she says. And because each state also has a bank regulator, she notes, “if you’re a fintech innovator, you have to go state by state and spend millions of dollars and take years” to comply with a spool of red tape pertaining to nonbanks.

At the federal level, the current system— which includes the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)—developed over time in a piecemeal fashion, largely through legislative responses to economic panics, shocks and emergencies. “For historical reasons,” Barefoot remarks, “we have a lot of agencies” regulating financial services.

For exhibit A, look no further than the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau created amidst the shambles of the 2008-2009 financial crisis by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. Built ostensibly to preserve safety and soundness, the agencies have constructed a moat around the banking system.

Karen Shaw Petrou, managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics, a Washington, D.C. consultancy, is a banking policy expert who frequently provides testimony to Congress and regulatory agencies. She wrote recently that the country’s banking sector has been protected from the kind of technological disruption that has upended a whole bevy of industries.

“The only reason Amazon and its ilk may not do to banking, brokers and insurers what they did to retailers—and are about to do to grocers and pharmacies,” she observed recently in a blog—“is the regulatory structure of each of these businesses. If and how it changes are the most critical strategic factors now facing finance.”

Cornelius Hurley, a Boston University law professor and executive director of the Online Lending Policy Institute, is especially critical of the 50-state, dual banking system. State bank regulators oversee 75 percent of the country’s banks and are the primary regulators of nonbank financial technology companies. “The U.S. is falling behind other countries that are much less balkanized,” Hurley says. “Our federal system of government has served us well in many areas in our becoming a leading civil society. It’s given us NOW (Negotiable Order of Withdrawal) accounts, money-market accounts, automatic teller machines, and interstate banking. But now it’s outlived its usefulness and has become an impediment.”

Take Kabbage, which actually avoids a lot of regulatory rigmarole by virtue of its partnership with Celtic Bank, a Utah-chartered industrial bank. The association with a regulated state bank essentially provides Kabbage with a passport to conduct business across state lines. Nonetheless, Kabbage has multiple, incessant, and confusing dealings with its bank overseers in the 50 states.

“Where the states get involved,” says Taussig, “is on brokering, solicitation, disclosure and privacy. We run into varying degrees of state legislative issues that make it hard to do business. Right now we’re plagued by what’s been happening with national technology actors on cybersecurity breaches and breach disclosures. We are required to notify customers. But some states require that we do it in as few as 36 hours, and in others it’s a couple of months. We’ve lobbied for a national breach law of four days,” he adds, which would “make it easier for everyone operating across the country.”

Then there’s the meaning of “What is a broker?’” says Taussig, who as a regulatory compliance expert at Kabbage sees his role as something of an emissary and educator to regulators and politicians, the news media, and the public. “The definitions haven’t been updated since the 1950s and now we have wildly different interpretations of brokering and solicitation,” he says. “The landscape has changed with e-commerce and each state has a different perspective of what’s kosher on the Internet.”

Washington State is a good example. It’s one of a handful of jurisdictions in which regulators confine nonbank fintechs to making consumer loans. In a kabuki dance, fintech companies apply for a consumer-lending license and then ask for a special dispensation to do small-business lending.

And let’s not forget New Mexico, Nevada and Vermont where a physical “brick-and-mortar” presence is required for a lender to do business. Digital companies, Taussig says, would have to seek a waiver from regulators in those states. “Many companies spend a lot of money on billable hours for local lawyers to comply with policies and procedures,” Taussig reports, “and it doesn’t serve to protect customers. It’s really just revenue extraction.”

All such restraints put fintechs at a disadvantage to traditional financial institutions, which by virtue of a bank charter, enjoy laws guaranteeing parity between state-chartered and federally chartered national banks. The banks are therefore able to traverse state lines seamlessly to take deposits, make loans, and engage in other lines of business. In addition, fintechs’ cost of funds is far higher than banks, which pay depositors a meager interest rate. And banks have access to the Fed discount window, while their depositors’ savings and checking accounts are insured up to $200,000.

The result is a higher cost of funds for fintechs, which principally depend on venture capital, private equity, securitization and debt financing as well as retained earnings. And that translates into steeper charges for small business borrowers. A fintech customer can easily pay an interest rate on a loan or line of credit that’s three to four times higher than, say, a bank loan backed by the U.S. Small Business Administration.

Kabbage, for example, reports that its average loan of roughly $10,000 typically carries an interest rate of 35%-36%. It’s credits are, of course, riskier than the banks’. The company does not report figures on loans denied, Taussig told AltFinanceDaily, but Stanford’s Singleton says that the fintech industry’s denial rate is roughly 50 percent for small business loans. “Fintechs have higher costs of capital and they’re also facing moderate default rates,” notes Singleton. “They’re not enormous, but fintechs are dealing with a different segment. Small businesses have much more variability in cash flows, so lending could be riskier than larger, established companies.”

Even so, venture capitalists continue to pour money into fintech start-ups. “I’ve gone to several conferences,” Singleton says, “and everywhere I turn I’m meeting people from a new fintech company. One of the striking things about this space,” he adds, “is that there are lot of aspiring start-ups attacking very specific, very narrow issues. Not all will survive, but someone will probably acquire them.”

Even so, venture capitalists continue to pour money into fintech start-ups. “I’ve gone to several conferences,” Singleton says, “and everywhere I turn I’m meeting people from a new fintech company. One of the striking things about this space,” he adds, “is that there are lot of aspiring start-ups attacking very specific, very narrow issues. Not all will survive, but someone will probably acquire them.”

Contrast that to the world of banking. Many banks are wholeheartedly embracing technology by collaborating with fintechs, acquiring start-ups with promising technology, or developing in-house solutions. Among the most impressive are super-regionals Fifth Third Bank ($142.2 billion), Regions Financial Corp. ($123.5 billion), and BBVA Compass ($69.6 billion), notes Miami-based bank consultant Charles Wendel. But many banks are content to cater to familiar customers and remain complacent. One result is that there’s been a steady diminution in the number of U.S. banks.

Over the past ten years, fully one-third of the country’s banks were swallowed whole in an acquisition, disappeared in a merger, failed, or otherwise closed their doors. There were 5,670 federally insured banks at the end of 2017, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., a 2,863-bank, 33.5% decrease from the 8,533 commercial banks operating in the U.S. in 2007.

It does appear that, to paraphrase an old expression, many banks “are going out of style.” In recent years there have been more banking industry deaths than births. Sixty-three banks have failed since 2013 through June while only 14 de novo banks have been launched. In Texas, which is known for having the most banks of any state in the country, only one newly minted bank debuted since 2009. (The Bank of Austin is the new kid on the Texas block, opening in a city known as a hotbed of technology with its “Silicon Hills.”)

One reason there’s so little enthusiasm among venture capitalists and other financial backers for investing in de novo banks is that regulators are known to be austere. “If you’re a company in the U.S.,” says Matt Burton, a founder of data analytics firm Orchard Platform Markets (which was recently acquired by Kabbage), “and you tell regulators that you want to grow by 100 percent a year – which is the scale you must grow at to get venture-capital funding – regulators will freak out. Bank regulators are very, very strict. That’s why you never hear about new banks achieving any sort of scale.”

But while bank regulators “are moving sluggishly compared to the rest of the world” in adapting to the fintech revolution, says Singleton, there are numerous signs that the status quo may be in for a surprising jolt. The Treasury Department is about to issue (possibly by the time this story is published) a major report recommending an across-the-board overhaul in the regulatory stance toward all nonbank financials, including fintechs. According to a report in The American Banker, Craig Phillips, counselor to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, told a trade group that the report would address regulatory shortcomings and especially “regulatory asymmetries” between fintech firms and regulated financial institutions.

Christopher Cole, senior regulatory counsel at the Independent Community Bankers Association—a Washington, D.C. trade association representing the country’s Main Street bankers—told AltFinanceDaily that, among other things, the Treasury report would likely recommend “regulatory sandboxes.” (A regulatory sandbox allows businesses to experiment with innovative products, services, and business models in the marketplace, usually for a specified period of time.)

That’s an idea that fintech proponents have been drumming enthusiastically since it was pioneered in the U.K. a few years ago, and it’s something that the independent bankers’ lobby, whose member banks are among the most threatened by fintech small-business lenders, says it too can support. Treasury’s Phillips “has said in the past that he’d like to see a level playing field,” the ICBA’s Cole says. “So if (regulators) are going to allow a sandbox, any company could be involved, including a community bank. We agree with him, of course, because we’d like to take advantage of that.”

In March, 2018, Arizona became the first state to establish a regulatory sandbox when the governor signed a law directing that state’s attorney general (and not the state’s banking regulator) to oversee the program. The agency will begin taking applications in August with approval in 90 days, says Paul Watkins, civil litigation chief in the AG’s office. Watkins told AltFinanceDaily that he’s been most surprised so far by “the degree of enthusiasm” from overseas companies. With the advent of the sandbox, he adds, “Landlocked Arizona has become a port state.”

The OCC, which is part of the Treasury Department, may also revive its plan to issue a national bank charter to fintechs, sources say (EDITOR’S NOTE: This had not yet been implemented before this story went to print. The OCC is now accepting such applications) – a hugely controversial proposal that was put on ice last year (and some thought left for dead) when former Commissioner Thomas J. Curry’s tenure ended last spring. At his departure, the fintech bank charter faced a lawsuit filed by both the New York State Banking Department and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. (Since then, the lawsuit was tossed out by the courts on the ground that the case was not “ripe” – that is, it was too soon for plaintiffs to show injury).

The OCC, which is part of the Treasury Department, may also revive its plan to issue a national bank charter to fintechs, sources say (EDITOR’S NOTE: This had not yet been implemented before this story went to print. The OCC is now accepting such applications) – a hugely controversial proposal that was put on ice last year (and some thought left for dead) when former Commissioner Thomas J. Curry’s tenure ended last spring. At his departure, the fintech bank charter faced a lawsuit filed by both the New York State Banking Department and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. (Since then, the lawsuit was tossed out by the courts on the ground that the case was not “ripe” – that is, it was too soon for plaintiffs to show injury).

Taussig, the regulatory expert at Kabbage, reports that the Comptroller of the Currency, Robert J. Otting, has promised “a thumbs-up or thumbs-down” decision by the end of July or early August on issuing fintechs a national bank charter. He counts himself as “hopeful” that OCC’s decision will see both of the regulator’s thumbs pointing north.

The Conference of State Bank Supervisors, meanwhile, has extended an olive branch to the fintech community in the form of “Vision 2020.” CSBS touts the program as “an initiative to modernize state regulation of non-bank financial companies.” As part of Vision 2020, CSBS formed a 21-member “Fintech Industry Advisory Panel” with a recognizable roster of industry stalwarts: small business lenders Kabbage and OnDeck Capital are on board, as are consumer lenders like Funding Circle, LendUp and SoFi Lending Corp. The panel also boasts such heavyweights in payments as Amazon and Microsoft.

Working closely with the fintech industry is a “key component” of Vision 2020, Margaret Liu, deputy general counsel at CSBS, told AltFinanceDaily in a recent telephone interview. CSBS and the fintech industry are “having a dialogue,” she says, “and we’re asking industry to work together (with us) and bring us a handful of top recommendations on what states can do to improve regulation of nonbanks in licensing, regulations, and examinations.

“We want to know,” she added, ‘What the main friction points are so that we can find a path forward. We want to hear their concerns and talk about pain points. We want them to know the states are not deaf and blind to their concerns.”